Take a deep breath: The technician’s role in respiratory emergencies

Shawna Cosgrove, CVT, VTS (ECC)

Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, MA

Posted on 2017-08-16 in Emergency & critical care

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the essential first step in treating any emergency that enters your hospital. This is even more vital in the case of respiratory emergencies. Critical thinking is the ability to rationally make a decision regarding the patient on the basis of investigation, analysis and evaluation. This is imperative to our goal as technicians to provide excellent patient care at all times. This is a skill not easily taught but is something that all technicians should strive to develop and improve upon. Our jobs are often an exercise in problem solving, especially when working with the most critical of emergencies.

Just as vital as developing and implementing good critical thinking skills, is developing a culture within your hospital of respect to all members of the veterinary team as a vital part of the patient’s healthcare. The key to such a culture is developing clear and open communication between the technicians and the doctors. A team unit in any ER situation will have a much better outcome overall than a disjointed unit of Doctors and technicians working separately from one another.

Treating Respiratory Emergencies

This task can often be a challenge for any technician or ER team member. After all, our goals often are in direct conflict with one another. On one hand, we must always be diligent to minimize stress to these patients, while on the other hand we need to obtain diagnostics in order to determine the problem and begin treatment. This is never an easy feat, but is one that the technician can play a vital role in, by making decisions along the way that will provide that patient with the best outcome possible.

Patient presentation

Any respiratory emergency that enters your hospital should automatically be placed high on the triage scale at a I or II on a scale of I-IV. Sometimes the signs are very subtle and the pet owner may give a presenting complaint that has nothing to do with the actual problem. It’s our job as technicians to use our critical thinking skills to find the hidden respiratory signs that sometimes we are presented with. More often than not though, our patients make it a bit easier and their respiratory signs are very evident upon presentation. Knowing what signs to look for and being able to make a very quick assessment of these patients allows us to begin treating the problem right away.

The initial assessment of the respiratory patient is the technician’s first opportunity to play a vital role in the patient’s treatment. Being able to recognize the various signs associated with different respiratory emergencies and alert the ER team to the patient’s status and needs can help to expedite that patient receiving the appropriate care and treatments quickly. While a TPR and physical assessment of our patient is an important step, many concerning signs can be noticed by the technician upon just a brief observation of that patient. Signs we may see vary from restlessness, anxiety, abnormal postures, a dazed appearance, tachypnea, paradoxical abdominal movement, open mouth breathing, loud breathing and coughing. Any patient assessed with respiratory compromise and in lateral recumbency can indicate that this patient is seriously compromised.

For a technician to understand and recognize abnormal signs they must first gain a good understanding of what is normal. A basic understanding of the respiratory tract and its function will assist the technician in their understanding of the common respiratory diseases and emergencies that we often see present in our hospitals.

The Respiratory system

The main function of the respiratory system is to facilitate gas exchange between the lungs and the circulatory system. This gas exchange provides the body and its tissues with oxygen that is taken in during inspiration and removes carbon dioxide during expiration. Oxygen is taken in through the nose or mouth, past the pharynx and into the trachea. The trachea divides at the carina into two bronchi and then enters the lungs. Once in the lung each bronchus branches off into smaller bronchioles which eventually end in clusters of alveoli. It’s here within the alveoli that gas exchange occurs at the alveolar-capillary membrane. Oxygen that is inspired into the alveoli, diffuses across this membrane where it enters the capillaries and binds to hemoglobin in the red blood cells. The oxygen is then transported to the tissues as blood is pumped through the body. The oxygen molecules separate from the hemoglobin and then diffuse into the tissue cells. This aids in the cells production of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) which is then used for cellular energy. CO2 is the main byproduct of cellular metabolism. The CO2 is eventually transported back to the lungs where it is diffused back into the alveoli and leaves the body via exhalation.

Plan!

No matter what our diagnosis or suspected diagnosis may be, the plan as to how we will proceed with obtaining diagnostics and treatment for these patients is the thing that often will be the difference between successful treatment of the patient or respiratory arrest and often death. Respiratory patients more than any other emergency patient we may see, are the most at risk for the stress of treatment to cause them to deteriorate quickly. A patient not handled carefully can often go from mild respiratory signs to respiratory arrest if the treatment plan puts too much stress on the patient. The goal should always be to minimize stress to these patients. This means working in a calm manner, with minimal handling and restraint. Often light sedation can aid the veterinary team in obtaining important diagnostics without causing harm to the patient. We may even at times decide that the risks of performing certain diagnostics and treatments are not worth risking further compromise to the patient. In these cases, we may hold off on things like gaining IV access until a patient is in a more stable situation and we feel they can handle the stress of placing an IV catheter. It’s in these situations that our critical thinking skills come into play as technicians. It’s never wrong to re-evaluate a treatment plan and try to find a better plan for that patient. Not all cases are the same and one treatment plan may work well for one patient and end in disaster for another.

Always be prepared

Having your staff always be prepared to treat respiratory patients when they enter your hospital is essential. Being ready to provide proper oxygen supplementation, as well as being prepared for rapid intubation, thoracocentesis and arrest scenarios will ensure your team is always at the ready. For both ER facilities and non-ER facilities it’s beneficial to hold emergency drills from time to time to allow your team the chance to “practice” getting ready for these situations so that when the real deal comes in everyone knows what to do.

Oxygen supplementation is one of the most important therapies we can provide, with little to no stress on the patient. There are many methods of which oxygen can be provided to our patients. Every clinic and hospital should be able to provide basic oxygen supplementation.

- Oxygen hoods-one can easily make an oxygen hood from an Elizabethan collar. They tend to work better in dogs, while cats tend not to tolerate them as well. You can easily make a hood by covering the ventral portion of the e-collar 75% with plastic wrap. Run the oxygen tubing along the inside of the collar and secure in place with tape ventrally. Oxygen levels of >60% can be achieved via this method when done correctly.

- Oxygen cages-are very easy to use. Place your patient in, close the door and walk away. While these are easy and convenient, they do have drawbacks. The main one is it can take some time for the oxygen levels to get up to 40% or more. Also, remember that each time you open the door to work on your patient that the oxygen escapes and needs to build back up again. You have to also be careful with larger sized patients as these cages can become quite warm and humid and cause the patient to become hyperthermic. If you have a climate controlled critical care oxygen cage this is not an issue. Placing ice in the cage can help some with this problem.

- Flow by oxygen-can be very effective and useful while you are attempting to work on your patient. Some patients, however, do not like t feeling of air blowing on their face so don’t set the flow rates too high. Using a mask if tolerated by the patient can make this method even more effective.

- Nasal cannula-well tolerated by some dogs and cats.

- Nasal catheter-one of the most effective ways to administer oxygen. Used primarily for our dog patients. A red rubber catheter is placed into the ventral nasal meatus and then is secured with either sutures or staples. Some patients will require light sedation to allow these to be placed, but often the patient is so focused on trying to ventilate, they are remarkably tolerant of the procedure.

Blood Gas analysis

Not all clinics have the ability to run in house blood gases. If you do have this ability it can be a useful tool in evaluating your patient’s ability to oxygenate and ventilate. The findings of your blood gas can aid in making treatment decisions for your respiratory patient. While the analysis of blood gases can be complex, technicians should strive to understand the basics of how to interpret your blood gas results.

Venous blood gases while useful, do not give us a great picture of the patient’s oxygenation status. They can give us information on the patient’s ability to ventilate as well as their metabolic status, but to assess oxygenation arterial blood gas analysis is necessary.

If you or someone at your clinic is proficient in arterial sampling and you have a blood gas analyzer, then you are ready to run an arterial blood gas. Arterial sampling is most often performed on the dorsal pedal or femoral arteries. Important to keep in mind once you draw your sample is to run it right away and to not agitate or mix your sample, as mixing with the room air can alter your results.

The values that are going to tell us the most about our patient’s oxygenation status are the PaO2 (partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood and the PaCO2 (partial pressure of CO2 in the arterial blood) evaluated the patient’s ventilation ability. Normal PaO2 at an FiO2 of 21% should be at least 80 mmHg. Less than 80 mmHg is considered hypoxemia and severe hypoxemia at <60 mmHg. Cyanosis usually is not evident until the PaO2 is less than 50 mmHg.

A PaCO2 of 35-45 indicates normal ventilation. Greater than that can indicate hypoventilation or hypercapnia. There are a few calculations we can make with our ABG results. One of the easier ones is the PaO2/FiO2 ratio. This equation can help us decide if our oxygen supplementation is resulting in adequate oxygenation for our patients. If we have a patient in an oxygen cage at an FiO2 of 40% (0.4) and our PaO2 is 98 mmHg, then our oxygenation index is 98/0.4=245. Results >300 indicate acceptable oxygenation and <300 we should reassess our patient’s oxygenation needs.

Common Emergency Respiratory conditions

Upper airway conditions

Laryngeal paralysis

A condition where the degeneration of nerve tissue innervates the laryngeal muscles causing a partial or complete failure of the arytenoids to abduct and adduct during inspiration and expiration. This condition is more commonly seen in larger breed dogs.

Clinical signs-progressive inspiratory stridor, “noisy” breathing, changes in the dog’s bark, heat and exercise intolerance, panting, tachypnea, dyspnea and cyanosis. These patients often present when they are having an “episode” of dyspnea and present in severe distress, collapse and cyanosis. These patients also are prone to aspiration pneumonia.

The technician’s first goal is to get that patient oxygen! Flow by is usually the quickest and easiest method for these patients while you work on them. Ultimately these patients need sedation at the very minimum and often require rapid induction and intubation. The technician should never be afraid to suggest that the patient is in enough distress to warrant these next steps. Once the patient is receiving oxygen and sedation has been administered, next steps may be to actively cool the patient if necessary (although often just sedation and intubation is enough to begin to lower their body temp). Often administering corticosteroids is also done to assist with inflammation. Once we are out of the emergent phase of presentation, further technician goals should be to keep this patient calm and quiet for the remainder of their stay in the hospital. Often once patients are breathing comfortably again, they are place on Butorphanol CRI’s to assist in keeping them calm and stress free.

Brachycephalic syndrome

A condition associated with our brachycephalic dog breeds that is caused by their narrow tracheas, elongated soft palates, stenotic nares and everted saccules. All of these together cause a reduction of airflow to the lungs. Frequently these patients present in distress on hot and humid days, or after times of stress and exercise. Similar to the lar par patient these patients present similarly with hyperthermia, tachypnea, dyspnea, cyanosis, respiratory stridor and hypercapnia. Treatment consists of sedation, often requiring rapid sequence intubation, administration of corticosteroids and oxygen supplementation. These animals will often tolerate being intubated and keeping a tube in place with just mild sedation. Aspiration pneumonia is also common in these patients. Often these patients cannot be extubated without going back into respiratory distress and need corrective surgery to address the brachycephalic abnormalities.

The technician’s role in these patients is similar to the lar par patient. Brachycephalic breeds should never be put under stress while in the hospital. Often these patients come in for another reason and escalate into a respiratory crisis due to stress. If you feel your patient is becoming stressed, talk to your Doctor and suggest some sedation to reduce the risk of the patient becoming dyspneic. While these patients are intubated they can develop a lot of laryngeal inflammation and swelling. We can attempt to combat this by packing the area with gauze soaked in hypertonic saline or at even green tea can aid in reducing inflammation. The technician should also be monitoring these patients for hyperthermia during times of stress.

Pulmonary conditions

Pulmonary edema

This is the development of fluid or secretions with in lungs. It can be cardiogenic (caused by a cardiac condition), or noncardiogenic (the result of an abrupt change in pressure within the thorax). Common causes of noncardiogenic edema are choking, strangulation, near drowning or after a dyspneic episode following a seizure.

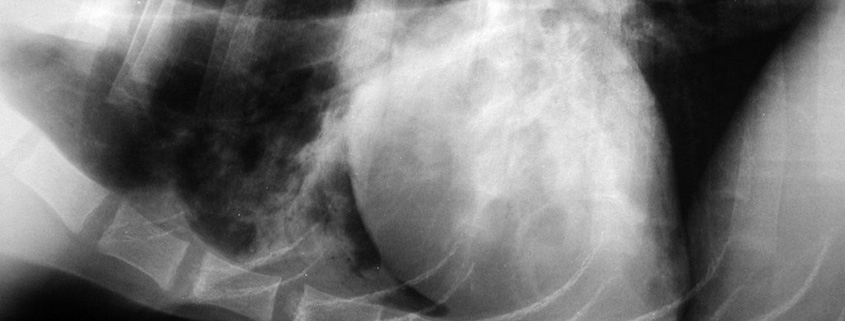

Patients with pulmonary edema may present with tachypnea, dyspnea, open mouth breathing, serous nasal discharge, a congested sound when they breath, and hypoxia. Auscultation of the lungs usually reveals loud pulmonary crackles.

Cardiogenic edema is not usually acute, but progressive although owner may wait until the patient is in distress to realize there is a problem.

The technician’s role in treating these patients lies mainly in the treatment plan and handling of these patients. If the dyspnea is only mild, we may be able to gain IV access and radiographs to definitively diagnose the pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure. More often these patients are in too much distress to safely do those things. Instead we often have to treat the patient before we can acquire all of the diagnostics we want. Oxygen is the first and most important thing the technician can provide this patient. Administering a diuretic such as Lasix is also usually essential to beginning to help these patients. If IV access is not possible in the emergent phase we can still administer Lasix IM, until the patient is in a better place to attempt placing an IV catheter. Technicians working on these patients need to keep their Doctor informed as to whether or not the treatment plan is “going well”. This is where developing that culture of a united front of Doctor and technician is vital for providing that patient with the best possible outcome.

Non-cardiogenic edema is treated with oxygen support and in severe cases mechanical ventilation.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia can be the presenting problem or secondary to another condition. It can be bacterial, fungal or viral in nature or caused by aspiration. Patients usually present with a history of coughing, lethargy, fever, tachypnea, dyspnea and nasal discharge. Diagnosis involves radiographs and often a transtracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage is performed to identify the microorganism and aid in appropriate antibiotic therapy.

The technician’s role in treating these patients usually involves oxygen supplementation, nebulization and coupage and supportive care. Nursing care and patient monitoring are important and recognizing trends and changes in the patient’s condition are important responsibilities for the technician caring for these patients.

Pleural space conditions

These may develop following trauma, coagulopathies, ruptured bullae or cardiac disease. Some types of pleural space conditions may be hemothorax, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, pyothorax and diaphragmatic hernia.

Being able to quickly prepare for many of these emergencies involves obtaining IV access, rapid setup for thoracocentesis and in severe cases set up for placement of a chest tube. The technician should also be providing oxygen supplementation and often patients require light sedation in order to perform the chest tap. In cases of hemothorax where a coagulopathy like rodenticide toxicity is a concern, often we will only tap the chest if the patient is severely compromised as the procedure itself may cause more hemorrhaging to occur. These patients ideally need a plasma transfusion to replace their clotting factors. If you have the ability to run in house PT/PTT panels, this can be quickly diagnosed.

Often times these patients are so severely compromised that we don’t have the luxury of diagnostic radiographs to confirm the existence of fluid or air in the pleural space and we are required to perform a therapeutic thoracocentesis to stabilize the patient. Often auscultation of the patient will reveal both quiet lung and heart sounds making us suspicious of pleural space disease. Don’t be afraid to do the chest tap without a radiograph if the patient is in enough distress and you suspect pleural space disease.

Traumatic conditions

Any type of trauma to the chest wall, lungs or airway can lead to respiratory compromise. Patients hit by car, animal attacks, falls and other traumas are at risk for sustaining injuries that will lead to respiratory compromise.

The most common trauma we see is probably the hit by car patient. They are at risk for pulmonary contusions, pneumothorax, hemothorax, flail chest, and diaphragmatic hernia. The trauma patient has a multitude of problems that need to be addressed beyond just the respiratory compromising injuries they may have sustained. Being prepared and working together as a team is extremely vital in these scenarios. Typically the most urgent needs to the patient are to address treating shock and any life-threatening injuries first. Any injuries resulting in severe respiratory compromise are injuries that should be attended to first. Giving clear direction to each member of the ER team will aid in your efforts being applied quickly for that patient.

Ongoing patient care

Once the emergent phase of care for each respiratory patient is successfully attended to, the patient will continue to require intensive nursing care and monitoring. The technician may be required to just observe the patient for a period of time or in extreme cases monitor the patient on mechanical ventilation. Developing good nursing skills and knowing what to look for in these patients is extremely important as the technicians are the ones most likely spending the most time with these patients in the hospital. The patient may require long term oxygen supplementation. Usually these patients should be handled minimally to reduce any added stress. Monitoring the patient’s respiratory rate and effort and making note of small changes in these parameters can go a long way in picking up on changes in their condition. Pulse ox can be fairly non-invasive tool to monitor oxygenation on these patients. Monitoring temperatures when dyspnea continues to be evident after hospitalization is important as well. Providing a spacious and cool cage or run in these cases and even utilizing ice or fans to assist in keeping them cool can be helpful. The most important tool the technician can use to aid in monitoring their patients is their own voice. Always remember you are your patient’s advocate and your Doctor is relying on you to make them aware of any concerns you have or any changes that you note in your patient’s condition. Your patient can’t speak for themselves so you must be their voice.

Further reading

- Small Animal Emergency and Critical care for Veterinary Technicians, Third edition, Andrea M. Battaglia and Andrea M. Steele

- Veterinary Technicians Manual for Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care, Christopher Norkus

- Study Guide to the AVECCT Examination, 2nd Edition, Rene Scalf

About the authorShawna Cosgrove has worked as a veterinary technician for 20 years. She graduated from SUNY Canton in NY with a A.S. in Veterinary Technology. She currently is a LVT in NY, a CVT in MA and a VTS in Emergency & Critical Care. For over a decade, Shawna has worked at Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital serving as the supervisor of the emergency and critical care department. Shawna is passionate about training technicians and seeks out formal and informal teaching opportunities. She is an active member of the Academy of Emergency and Critical Care Technicians, the MVTA, NAVTA and VECCS. Shawna has a love for emergency and critical care with areas of special interest in respiratory emergencies, ventilator medicine and trauma patients. |