Chemotherapy for solid tumors: What is the evidence?

Kendra Knapik, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology)

Peak Veterinary Referral Center, Williston, VT

Posted on 2017-08-08 in Oncology

In normal tissues there is a balance between cell birth and cell death. Disruptions in the factors that control this homeostasis can lead to uncontrolled cell growth or lack of cell death, thus producing a malignancy or tumor. Tumor cells show abnormal growth patterns and are not controlled by normal homeostatic growth controlling mechanisms.

Tumors are usually quite advanced before detection. A one centimeter tumor has about a billion cells. Unfortunately, tumors that are big enough to be detected tend to be less responsive to chemotherapy. Growth rates of tumors vary, and growth rate is important in determining chemotherapy response. The more actively dividing cells are more sensitive to chemotherapy. As a tumor gets larger, its growth tends to slow which is likely the result of increased cell death and decreased proliferation as tumor nutrition declines. Tumor cells outgrow their blood supply which results in a microenvironment with reduced oxygen and nutrients. Tumors are also characterized as having “genetic instability,” and multiple chemoresistant clones in a tumor increase with tumor volume as well (Goldie et al.).

Chemotherapy targets dividing cells by interfering with processes involved in progression through the cell cycle. The classic cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs affect DNA replication and cell division. Chemotherapy damages DNA, thus preventing replication and inducing apoptosis in some cases. Newer agents available to us now called signal transduction inhibitors (i.e. toceranib phosphate/Palladia) interfere with signaling processes that allow entry into the cell cycle and continued proliferation.

Chemotherapy can be used to treat visible tumors and also in the adjuvant setting. The adjuvant setting refers to treatment after the primary treatment i.e. surgery or radiation therapy. The goal of adjuvant treatment is to target micrometastasis in tumors that have a high risk of metastasis and also to prevent recurrence of the tumor locally in certain situations. Against measurable tumors, chemotherapy can be used in the neoadjuvant setting or in the palliative setting. The goal of neoadjuvant therapy is to downstage or cytodeduce a tumor before a primary treatment (i.e. surgery or radiation) to improve outcome. The goals of palliative chemotherapy are to improve clinical signs related to the primary tumor or metastasis. Chemotherapy used as such in the bulky or measurable disease setting is going to work most effectively for quickly growing tumors. Smaller tumors may respond better due to a higher growth fraction.

Commonly Treated Solid Tumors in Veterinary Medicine

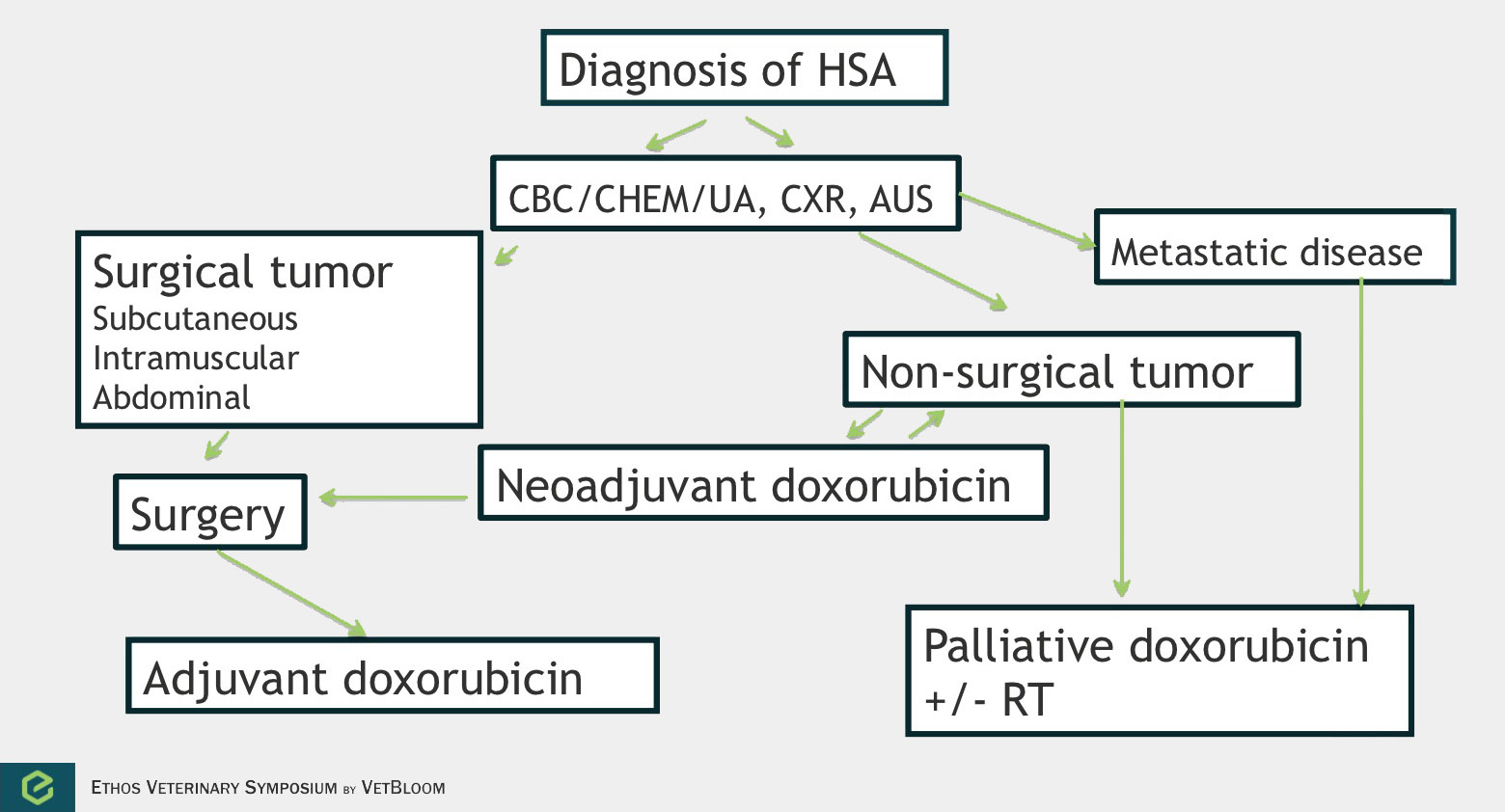

Flowchart for the diagnosis of hemangiosarcoma. Image courtesy of Carrie Hume, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology)

Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a highly aggressive and metastatic tumor that is derived from endothelial cells. Splenic hemangiosarcoma is the most common anatomic form, but hemangiosarcoma can develop in other organs including the skin/subcutis, liver, and heart. Chemotherapy can be used in the neoadjuvant, palliative, and adjuvant settings.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be considered for large subcutaneous and intramuscular tumors. In 18 dogs that were evaluated in the neoadjuvant setting, the response rate was 38.8-44% (partial and complete responses, with 1 dog having a complete response). Four dogs were able to go on and have complete surgical excision after chemotherapy (Wiley et al.). The time to tumor progression was 207 days when chemotherapy and surgery were used, and 83 days with chemotherapy only. Adequate local control (ALC) is defined as complete tumor resection or incomplete tumor resection followed by radiation. Achieving ALC has been found to provide the best chance of longer term control in subcutaneous/intramuscular tumors. Shiu et al. found that time to tumor progression was 202 days with ALC versus 72 days with no ALC, similar to Wiley et al.’s findings using neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery.

Palliative chemotherapy can be considered with subcutaneous and intramuscular tumors, atrial tumors, and tumors in which metastasis has occurred.

In splenic hemangiosarcoma, the median survival time after splenectomy alone is 19-86 days. Doxorubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to modestly improve outcome, median survival time of 172-257 days. One small study that used low dose chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and piroxicam (metronomic chemotherapy) in the adjuvant setting in 9 dogs compared to historical controls that received doxorubicin showed similar outcomes (Lana et al.). A couple newer retrospective studies have looked at doxorubicin chemotherapy followed by metronomic chemotherapy. There may be some value in metronomic chemotherapy in these patients (Finotello et al., Wendelburg et al.).

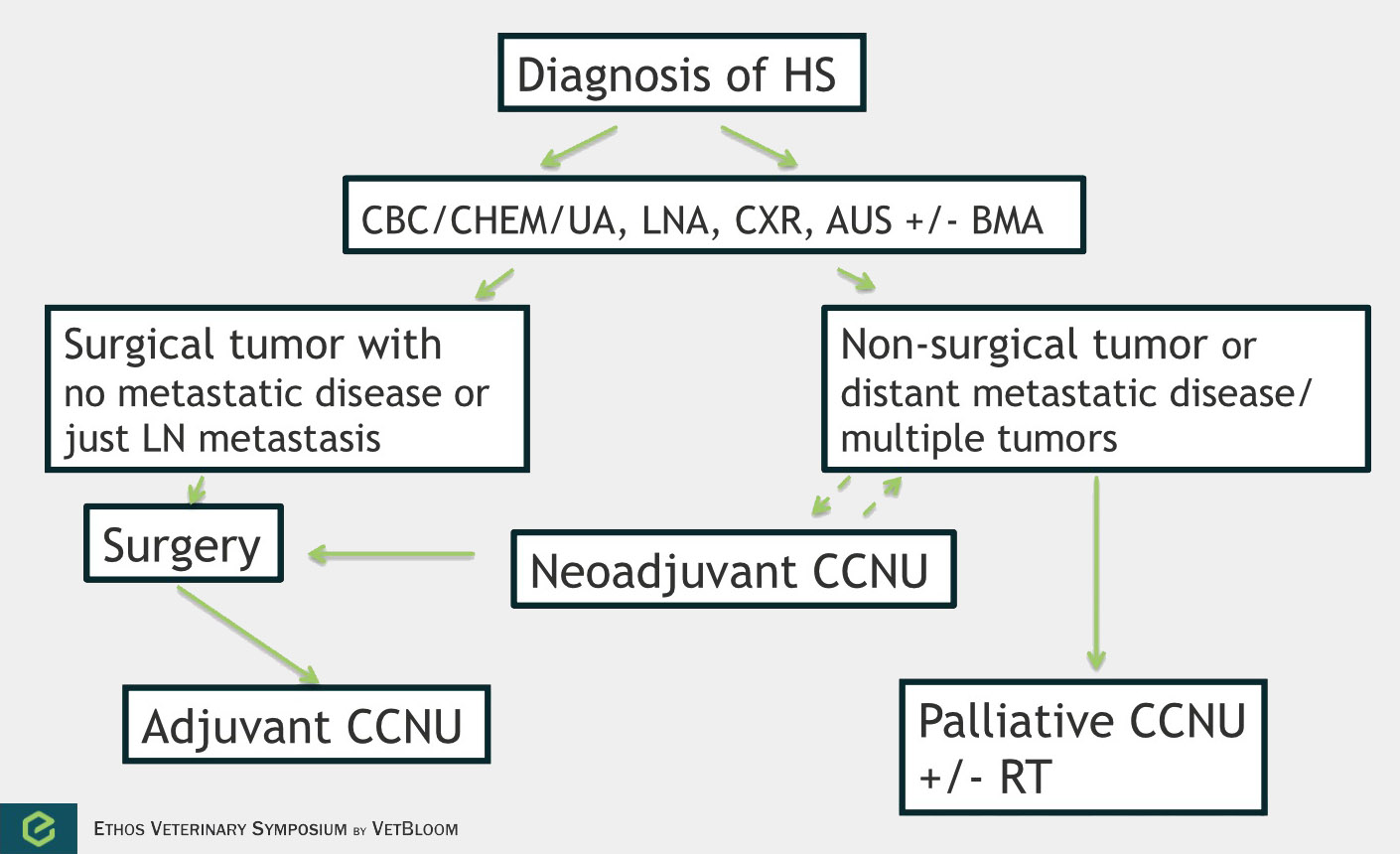

Flowchart for the diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma. Image courtesy of Carrie Hume, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology)

Histiocytic sarcoma

Histiocytic sarcoma is an aggressive and highly metastatic (70-90%)cancer of histiocytic cells. This disease has been reported toaffect the lungs, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, stomach, pancreas, mediastinum, skin,skeletal muscle, central nervous system, bone, bone arrow, nasal cavity, and eyes.There is both a localized form of histiocytic sarcoma and a disseminated form. Chemotherapy is most commonly used in the adjuvant or palliative setting, but neoadjuvant chemotherapy could be considered in large non-disseminated tumors.

In a prospective study of 14 dogs, the overall response rate was 29% with a median response of 96 days(Rassnick et al.). 3 dogs had a complete response (54-269 days), and 3 dogs had a partial response (78-112 days).A response rate of 46% was noted in a retrospective study of 59 dogs (Skorupskiet al.). The overall survival time was 106 days, and dogs with ALC of the tumor lived 433 days or longer (n=3). Skorupski et al. then looked at using CCNU as an adjuvant treatment. In 16 dogs with ALC, the median survival time for all dogs was 568 days.Flow chart for approach of canine histiocytic sarcoma:

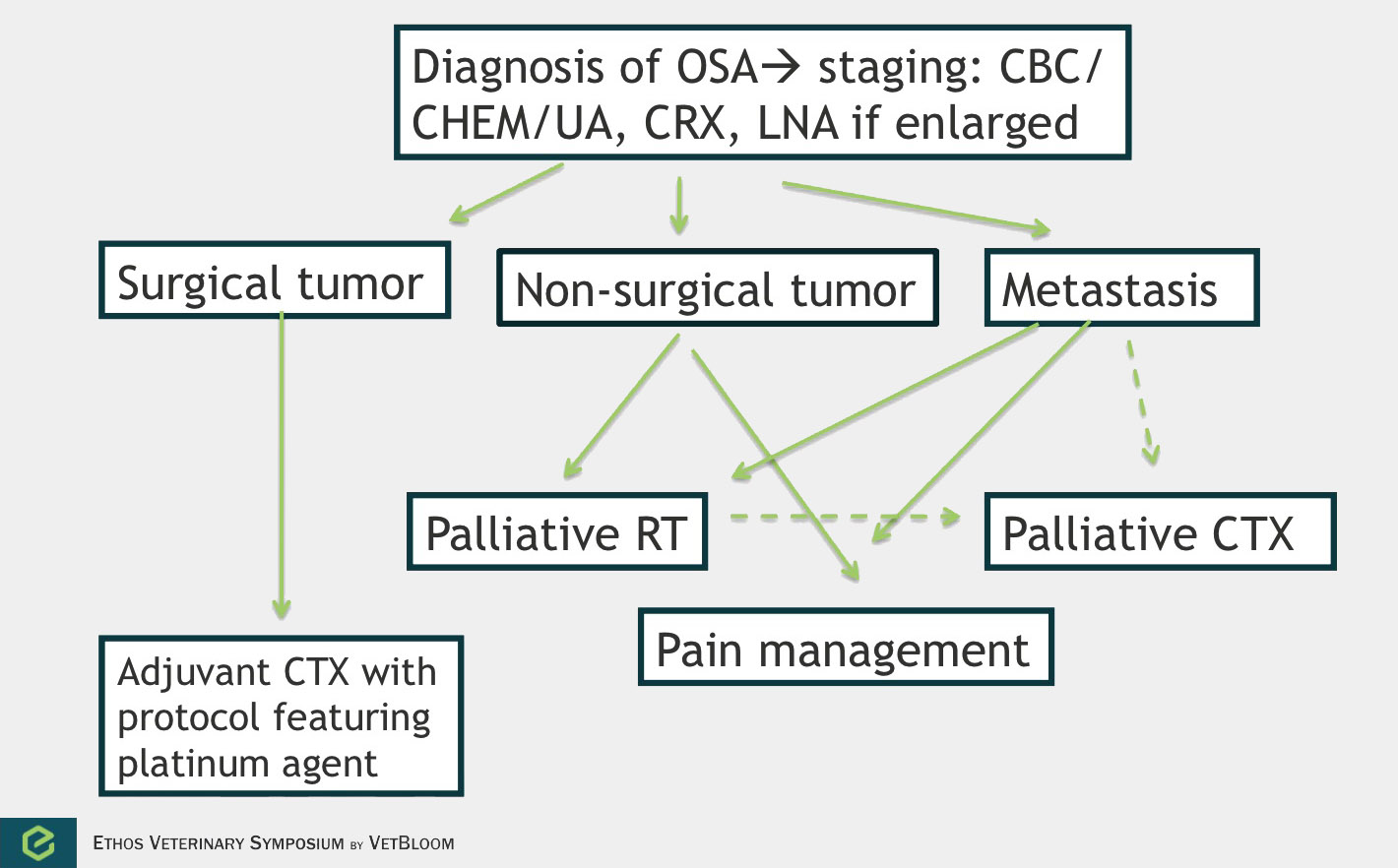

Flowchart for the diagnosis of osteosarcoma. Image courtesy of Carrie Hume, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology)

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumor in dogs. It is a locally aggressive tumor with a high metastatic rate. The main use of chemotherapy is in the adjuvant setting. However, chemotherapy can also be used in the palliative setting. No data exists that shows improved survival in dogs given chemotherapy prior to surgery. 90% of dogs will die because of metastatic disease within 1 year when treated with surgery alone (Spodnick et al.). The use of adjuvant platinum chemotherapy has significantly improved survival times with 1 year survivals of 35-62% and median survival times of 235-413 days. Most dogs will still die because of their metastatic disease.

Cisplatin, carboplatin, and doxorubicin have been found to have efficacy in osteosarcoma in the adjuvant setting. Cisplatin is not commonly used however because it requires up to 6 hours of diuresis due to nephrotoxicity. Carboplatin has similar anti-tumor effects and is less nephrotoxic. Two studies examining doxorubicin as a single agent in the adjuvant setting for osteosarcoma showed very different outcomes. Berg et al. showed an outcome very similar to what is seen with platinum agents (1 year survival of 50%), and Madwell et al. showed a median survival of only 104 days. Combination protocols of alternating platinum drugs and doxorubicin have been examined with comparable results to single agent protocols. Chemotherapy can be considered in the adjuvant setting with non-appendicular tumors, especially if higher grade, but local disease control is usually more of an issue for these patients.

Palliative chemotherapy can be considered for metastatic disease or for the primary tumor that has not been treated with surgery. In a study that examined various injectable chemotherapy drugs to treat metastatic osteosarcoma (Ogilvie et al.), a response was seen in only 1 of 45 dogs (a partial response lasting 21 days). While response to injectable therapy has been disappointing in treating metastatic disease, a study evaluating the biological activity of Palladia in solid tumors demonstrated close to 50% clinical activity in 23 dogs with metastatic osteosarcoma (10 dogs with stable disease and 1 with a partial response) (London et al.). Treating a primary bone tumor with chemotherapy will not do much for pain control when given alone, but may be beneficial when given concurrently with radiation (Ramirez et al.).

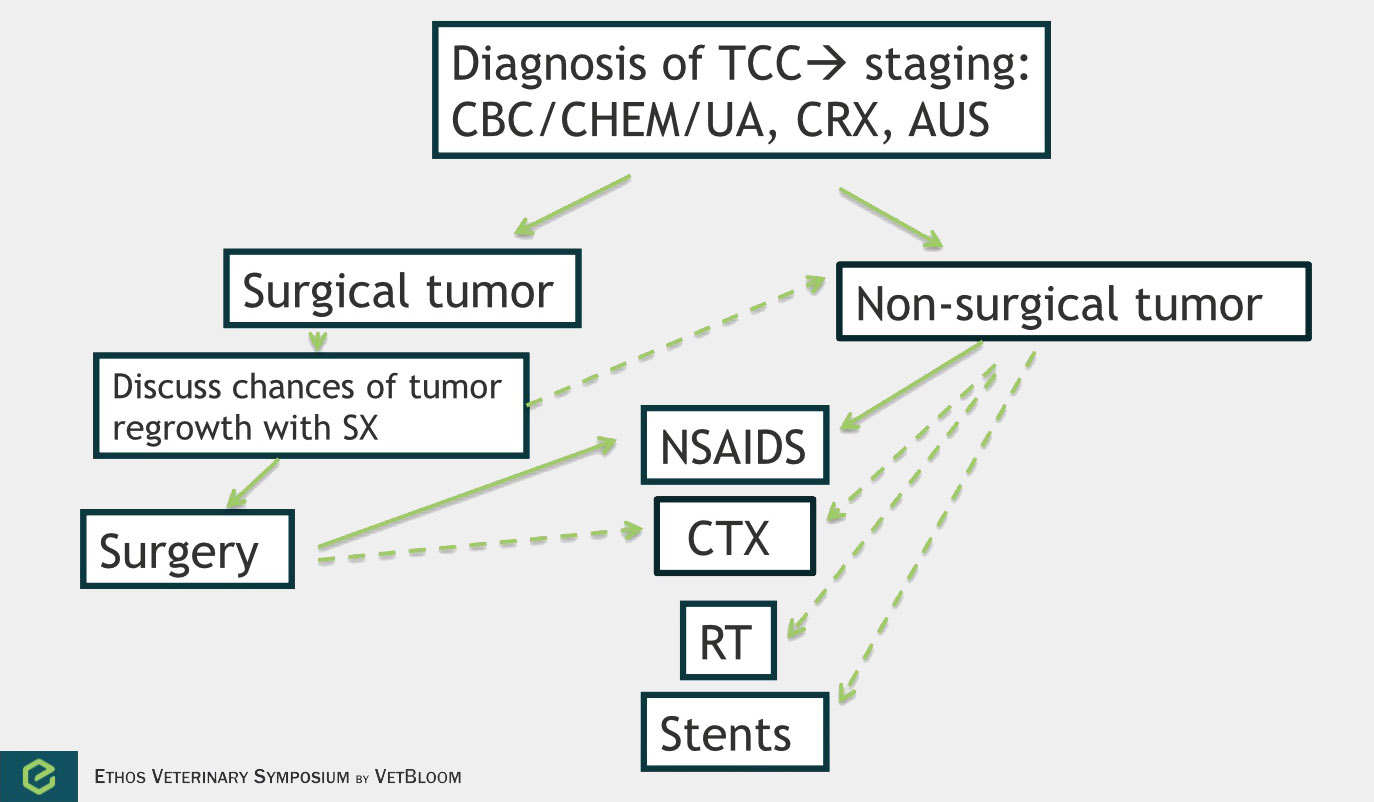

Flowchart for the diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma. Image courtesy of Carrie Hume, VMD, DACVIM (Oncology)

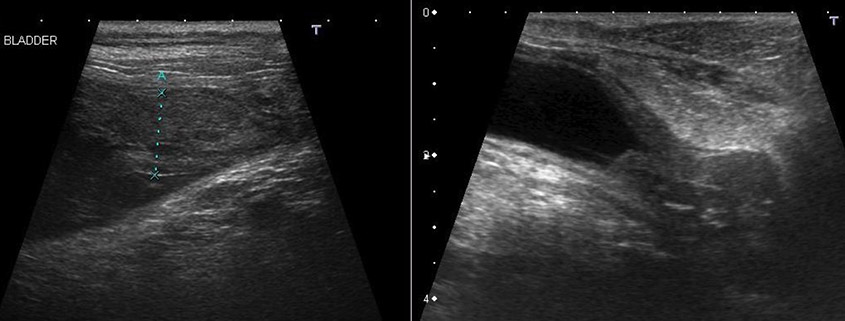

Transitional cell carcinoma

Transitional cell carcinoma is the most common form of canine urinary bladder cancer. Transitional cell carcinoma can affect the bladder, urethra, and prostate. It is a locally invasive tumor with moderate metastatic potential (16% have lymph node metastasis at diagnosis, 14% have distant metastasis at diagnosis, and 50% have metastasis at death) (Knapp et al). Chemotherapy is most commonly used palliatively, but should also be considered in the adjuvant setting. Studies evaluating treatment of transitional cell sarcoma by response and median survival time are difficult to evaluate. Response is often measured by ultrasound, and cystosongraphic measurements of canine bladder tumors have been found to vary significantly with operator and bladder tumor volume. Survival on the other hand is very much dependent on when and owner decides to euthanize.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended in all dogs with transitional cell carcinoma due to their anti-cancer activity and improvement of clinical signs. Intravenous/oral chemotherapy drugs that have shown responses include mitoxantrone, carboplatin, cisplatin, vinblastine, chlorambucil, and gemcitabine. These drugs are often given along with an NSAID to improve outcome. Use of these chemotherapy agents adjuvantly requires further study. There is a high rate of tumor regrowth following surgery, and chemotherapy may be more effective when treating minimal residual disease.

Further reading

- Berg et al. Results of surgery and doxorubicin chemotherapy in dogs with osteosarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;206(10):1555-60.

- Finotello et al. A retrospective analysis of chemotherapy switch suggests improved outcome in surgically removed biologically aggressive canine haemangiosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol 2016; Epub ahead of print.

- Goldie et al. The genetic origin of drug resistance in neoplasms: implications for systemic therapy. Cancer Research 1984;44:3643-3653.

- Hume et al. Cystosonographic measurements of canine bladder tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 2010;8(2)122-6.

- Knapp et al. Naturally-occurring canine transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A relevant model of human invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 2000;5(2):47-59.

- Lana et al. Continuous low-dose oral chemotherapy for adjuvant therapy of splenic hemangiosarcoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21(4):764-9.

- London et al. Preliminary evidence for biologic activity of toceranib phosphate (Palladia) in solid tumours. Ve Comp Oncol 2012;10(3):194-205.

- Madewell et al. Amputation and doxorubicin for treatment of canine and feline osteogenic sarcoma. Eur J Cancer 1978:14(3):287-93.

- Ogilvie et al. Evaluation of single-agent chemotherapy for treatment of clinically evident osteosarcoma metastasis in dogs: 45 cases (1998-1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;202(2):304-6.

- Ogilvie GK et al. Surgery and doxorubicin in dogs with hemangiosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 1996 10(6):379-84

- Ramirez et al. Palliative radiotherapy of appendicular osteosarcoma in 95 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1999;40 (5):517-22.

- Rassnick et al. Phase II, Open-Label Trial of Single-Agent CCNU in Dogs with Previously Untreated Histiocytic Sarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2010; 24:1528-1531.

- Shiu KB et al. Predictors of outcome in dogs with subcutaneous or intramuscular hemangiosarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011;238(4):472-9.

- Skorupski KA et al. CCNU for the Treatment of Dogs with Histiocytic Sarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:123-126.

- Skorupski et al. Long-term survival in dogs with localized histiocytic sarcoma treated with CCNU as an adjuvant to local therapy. Vet Comp Oncol 2009;7(2):139-14.

- Sorenmo et al. Chemotherapy of Canine Hemangiosarcoma with Doxorubicin and Cycophosphamide. J Vet Intern Med 1993;7:370-376.

- Sorenmo KU et al. Efficacy and toxicity of a dose-intensified doxorubicin protocol in canine hemangiosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2004 18(2):209-13.

- Spodnick et al. Prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma treated by amputation alone: 162 cases (1978-1988). J Am Vet Med Assoc1992;200(7);995-9

- Tannock I, Hill R, Bristow R, Harrington L. The basic Science of Oncology, 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2013.

- Wendelburg et al. Survival time of dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma treated by splenectomy with or without adjuvant chemotherapy: 208 cases (2001-2012). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015;247(4):393-403.

- Wiley JL et al. Efficacy of doxorubicin-based chemotherapy for non-resectable canine subcutaneous haemangiosarcoma. Vet Comp Onco 2010;8(3):221-33.

- Withrow SJ, Vail DM, Page RL. Small Animal Clinical Oncology, 5th ed. St. Louis MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

About the author

|

Dr. Kendra Knapik obtained her Bachelor of Science degree from Cornell University and her DVM from Colorado State. Kendra then completed a one-year general internship at Red Bank Veterinary Hospital in New Jersey. She completed her residency in oncology at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011.

Dr. Kendra Knapik obtained her Bachelor of Science degree from Cornell University and her DVM from Colorado State. Kendra then completed a one-year general internship at Red Bank Veterinary Hospital in New Jersey. She completed her residency in oncology at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011.