The yellow fellow: Evaluation of the icteric cat

Marion Haber, DVM, DACVIM

Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, MA

Posted on 2016-08-09

Icterus is the presence of yellow discoloration of non-pigmented body surfaces (i.e. mucous membranes, sclera, skin) or plasma, and this results from an accumulation of bilirubin in the blood stream.

Bilirubin pigment is derived from the breakdown of substances containing heme. The major source of heme is RBC hemoglobin. Unconjugated bilirubin is produced by the mononuclear/macrophage system in processing senescent red blood cells. This unconjugated bilirubin is usually taken up by the liver and conjugated with glucuronide allowing this combination to be highly water-soluble, which in turn allows elimination by the kidney. Most bilirubin is actually eliminated via the biliary system and it is this substance that colors bile green. Bilirubin is temporarily stored in the gall bladder. At meal times the gall bladder contracts and bile is discharged into the intestines. Some conjugated bilirubin is resorbed and recirculated, but most of it is metabolized by bacteria into other products, including sterocobilin and urobilinogen. Approximately 25% of urobilinogen is taken up into the portal vein to allow for renal elimination. In general, dogs have a lower renal bilirubin threshold due to their ability to process bilirubin in the renal tubules. Cats, on the other hand, have a high bilirubin threshold, which means that urine bilirubin is always abnormal in this species.

When evaluating the icteric feline patient, consideration should be given to evaluating for hemolytic anemia; however, most commonly the cause of icterus is related to hepatobiliary disease. Hepatic lipidosis is the most common liver disease in cats followed by chronic inflammatory disease and then neoplasia and hepatocellular necrosis.

Cholangitis

Inflammatory liver disease, specifically cholangitis, is the second most common liver disease in cats. The term of cholangitis is used as most cats, unlike in dogs, show primary inflammation around bile ducts and ductules. Certainly, there are cases where inflammation extends into the hepatic parenchyma and then the term cholangiohepatitis is appropriate. Inflammatory disease involving only the hepatic parenchyma appears to be rare but can be seen with toxoplasmosis or feline infectious peritonitis. Lymphocytic portal hepatitis is also described and may not be a primary hepatobiliary disease. Rather, it seems related to a reaction occurring elsewhere in the body; often blood work changes are mild and most cats have prolonged survival. Cholangitis is subdivided into three categories: neutrophilic (with acute and chronic forms), lymphocytic and cholangitis associated with liver flukes.

Neutrophilic cholangitis

Neutrophilic cholangitis can be subdivided into acute, where neutrophils predominate, and chronic where there tends to be mixed cellular infiltrate as well as biliary hyperplasia and possible periductal and bridging fibrosis. The acute form is thought to be caused by bacteria from the GI tract either via biliary uptake or hematogenously due to increased enterohepatic translocation of bacteria. The chronic form may reflect a chronic form of infection as well as inflammation. Rarely, protozoal infections (e.g. Toxoplasmosis) can be the cause of neutrophilic cholangitis. Most cats with neutrophilic cholangitis have a median age of 9 years and signs noted by owners include anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, and vomiting. Younger cats may be seen with the acute form. On physical examination, cats may have a fever, dehydration, icterus, pain and hepatomegaly. On blood work, most cats will have a neutrophilia although this is more common in the acute form. On the complete blood count, bands, neutropenia and anemia may also be appreciated but are less common. Chemistry profiles may show increased enzyme activities including ALT, AST, GGT and ALP as well as hyperbilirubinemia however normal enzyme concentrations can also be seen in these patients. Liver dysfunction and signs consistent with hepatic encephalopathy are rare in these patients. These laboratory findings except for the finding of neutrophilia are common among all categories of cholangitis. Also, common among the categories is the chance that ultrasound and radiographic evaluation may show no abnormalities. Abnormalities that may be noted with radiographs include hepatomegaly, which can also be noted with ultrasound. Ultrasound may also find hyperechoic hepatic parenchyma, dilated common bile duct and echogenic gallbladder contents. Thickened gallbladder wall may be noted and if this is identified bacterial cholecystitis should be a consideration. Most commonly Escherichia coli is cultured from bile or liver but other bacteria may include Enterococcus sp., Bacteroides spp, Clostridia spp, Staphylococcus, and alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus spp. Cultures should include aerobic and anaerobic modalities for both biliary as well as liver cultures although the rate of positive cultures can be low. Comorbidities are common in neutrophilic cholangitis and can include hepatic lipidosis due to prolonged anorexia however also commonly inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis, which also is referred to as feline triaditis syndrome. Gagne et al reported in 1999 that 83% of cats with cholangitis also had histologic evidence of inflammatory bowel disease and 50% had concurrent chronic pancreatitis. In cases of moderate to severe pancreatitis 35% of cases have been found to have evidence of bacterial DNA in the pancreas. It is possible that the same bacteria may be infection the biliary system as the pancreas because the pancreatic and common bile duct join to form one duct prior to emptying into the duodenum. Another consideration, however, is the fact that bacteria are found more commonly in the parenchyma of the pancreas leading to the possibility of hematogenous spread possibly related to enterohepatic translocation. Ultrasound changes of pancreatitis are more commonly seen with cats having neutrophilic cholangitis and these changes can include diffuse pancreatic enlargement and hypoechoic parenchyma. Definitive diagnosis requires a liver biopsy or biliary cytology and positive culture. Often, a presumptive diagnosis is made based on positive clinical response and blood work improvement.

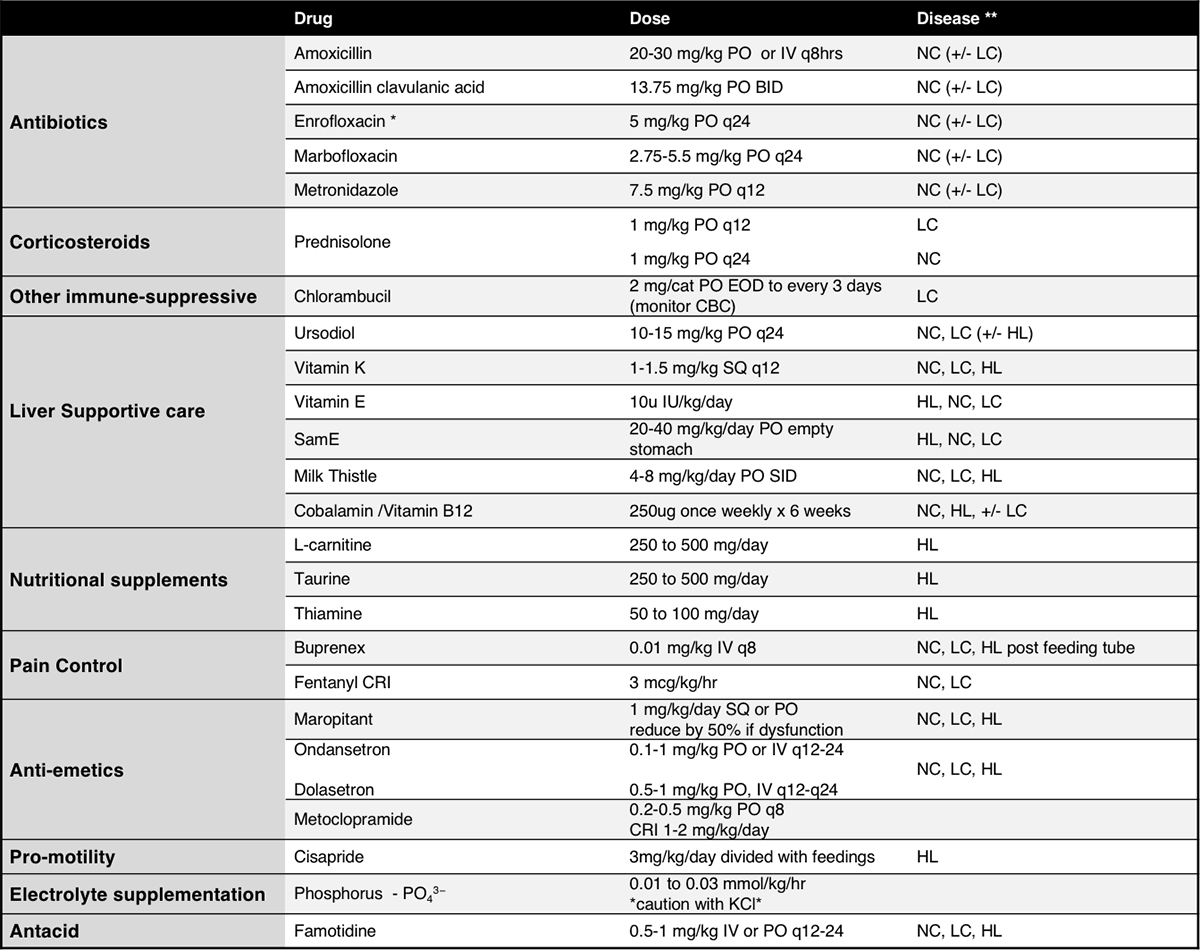

Treatment of neutrophilic cholangitis requires appropriate antibiotic choice ideally based on positive culture results, but often a choice is made based on the effectiveness of the antibiotic against most enteric gram-negative aerobes that also has good hepatic and biliary penetration. Examples include cephalosporins, amoxicillin or amoxillin-clavulanic acid. A fluoroquinolone may also be needed. To extend the spectrum to anaerobes as well as additional coliforms metronidazole should be considered. Treatment with antibiotics should be given for at least 4-6 weeks. Corticosteroid administration may need to be considered in those cases where the neutrophilic component is relatively minor or if there is a poor response to antibiotic therapy alone. In some cases, corticosteroids may also be treating underlying inflammatory bowel disease. These patients are often critical and require hospitalization. Fluid therapy and correction of electrolyte abnormalities including hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia is often necessary. With coagulopathies, Vitamin K supplementation is often necessary especially prior to procedures such as a biopsy or feeding tube placement. Nasoesophageal feeding tube placement may need to be considered if anorexia does not improve in the first 24 hours of treatment. Pain management may be needed especially in those cases of acute cholangitis. Often buprenorphine is chosen but for more severe continuous infusion with fentanyl may need to be considered. Controlling nausea and vomiting can be accomplished with Maropitant (Cerenia). Maropitant is a NK-1 receptor antagonist – in significant liver disease with hepatic dysfunction the dose may need to be reduced by 50%. Other option would include the dopaminergic antagonist metoclopramide (Reglan) that also may help with upper gastrointestinal ileus or the 5-HT3 antagonist ondansetron or dolasetron. Ursodeoxycholic acid can also be beneficial in these cases. It promotes bile flow, improves biliary secretion of bile acids and reduces the portion of hydrophobic bile acids, which have toxic effects on cellular membranes. Ursodeoxycholic acid also has potential anti-inflammatory, immune-modulatory and anti-fibrotic properties. Nutraceuticals that have antioxidant effects to help prevent damage from free radical formation causing cellular damage. Free radical formation can be caused by high concentrations of bile acids, accumulation of heavy metals and inflammation. Vitamin E and S-adenosylmethionine are used commonly. Consideration should also be given to the use of Vitamin C and phosphatidylcholine. Hepatoprotective effects are seen when milk thistle (or extract silymarin) is used. The active isomer silybin (available in the combination product Denamarin) is more orally bioavailable compared to silymarin and therefore consideration should be given to using this product.

Lymphocytic cholangitis

Lymphocytic cholangitis is a chronic disease that appears to be slowly progressive. In addition to lymphatic inflammation at the bile ducts, peribiliary fibrosis, portal B-cell aggregates or portal lipogranulomas can be noted. In one study by Warren et al in 2010 68.6 % of cases had a predominant dense T-cell population. In some cases, it is difficult to differentiate this type of cholangitis from lymphoma however PCR testing may be helpful.

Cats with lymphocytic cholangitis tend to be older with a median age of 11.5 years. Clinical signs include vomiting, lethargy, anorexia and weight loss. Signs can be intermittent and may wax and wane over months. Blood work and imaging findings have been described above. There is a possible geographic difference with studies from Europe showing a possible male predisposition as well as an overrepresentation of Norwegian Forest cats in one study. This study also showed a hyperglobulinemia and ascites as part of the clinical findings, which differs from cases described in North America. In another report by Lucke and Davies in 1984, there was an overrepresentation of young cats <4 years as well as the Persian breed.

Treatment in these cases is similar to those cats with neutrophilic cholangitis although corticosteroids are given to help control inflammation. Most commonly prednisolone is used because it is well absorbed and should improve laboratory findings as well as clinical signs. Tapering should not begin until 4 to 6 weeks of treatment and should not proceed more quickly than every 2 weeks and not more than 50% at a time. Ideally, a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg every 48 hours may need to continue for at least one month or long term depending on blood work. Long term steroid use can cause complications such as diabetes mellitus or congestive heart failure.

Hepatic lipidosis

Hepatic lipidosis is a disease that results from excessive lipid accumulation within hepatocytes. This lipid accumulation can lead to significant liver dysfunction with a cholestatic component. Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) induces peripheral lipolysis during periods of anorexia. Stress triggers greater amounts of catecholamines in circulation, which can also increase the HSL activation. This causes a significant increase in free fatty acids in the bloodstream, which are then taken up by the liver. These fatty acids are then either metabolized for energy, converted to triglycerides for storage or for secretion back into the circulation as very-low-density-lipoproteins. If delivery of fatty acids exceeds the liver’s capacity to metabolize them then excess storage occurs and hepatic lipidosis develops. Hepatic triglyceride content of a cat with hepatic lipidosis is 43% compared to a healthy cat where the hepatic triglyceride content is 1%. In more than 95% of cases of hepatic lipidosis there is a concurrent disease associated with the development of this condition. Common diseases include pancreatitis, cholangitis, small intestinal disease, neoplasia, kidney disease, and diabetes mellitus. Primary or idiopathic hepatic lipidosis occurs less commonly and is associated with inadequate food intake. This may be related to a reduction in food availability, aversion to new food by the cat, a stress in the life of the cat such as moving household or being at a boarding facility.

Most cats with hepatic lipidosis are middle-aged (median age 7 years) and overweight. There is no obvious gender or breed predilection. Most commonly they present with a history of anorexia that can range from 2 days to 2 weeks. Weight loss can be present and may also include muscle mass loss. Other findings by the owners can include lethargy or weakness, jaundice, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, or an unkempt, dull haircoat. On physical examination, patients may be lethargic, dehydrated and icteric in about 70% of cases. Hepatomegaly may be palpable. Ventroflexion of the neck as well, as well as generalized muscle weakness, can be noted in those patients with significant hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia and/or thiamine deficiency. These patients may also be found to bruise easily at venipuncture sites. In less than 5% of cases, signs of hepatic lipidosis may be appreciated, which may include ptyalism as well as mental dullness.

Diagnostic evaluation of these patients should include actual diagnosis of hepatic lipidosis as well as evaluation for underlying disease, which, among other tests, should include thyroid concentration, feline leukemia and feline immunodeficiency virus testing. Complete blood count may be normal but there are cases in which non-specific abnormalities are noted. These can include a mild to moderate normocytic, normochromic nonregenerative anemia, poikilocytosis, as well as Heinz bodies. Heinz bodies may be seen as cats are more susceptible to oxidative injury and this is augmented in cats with hepatic lipidosis. Poikilocytosis may be a result of altered red blood cell membrane lipids or metabolism or also oxidative stress affecting the red blood cell membrane. A mild leukocytosis and lymphopenia can also be noted in some patients. On a chemistry profile liver enzyme elevations are typical of those of a cholestatic pattern. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is increased to a higher magnitude above alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities. Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is inconsistently increased in these patients and if significant elevation is seen in this enzyme there should be a heightened concern for other diseases including pancreatic or biliary disease. In addition to liver enzyme changes electrolyte abnormalities are noted such as hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia and/or hypomagnesemia. Less commonly, hypercholesterolemia, hypoglycemia, hypoalbuminemia and low blood urea nitrogen may be observed. Urine testing will show bilirubinuria as well as lipiduria. Coagulation abnormalities are common in cats with hepatic lipidosis but bleeding complications are seen in less than 4% of patients. Prothrombin (PT) is most commonly elevated and improves in response to Vitamin K supplementation. Reduced enterohepatic circulation of bile acids from cholestasis leads to reduced absorption of fat-soluble vitamins including Vitamin K.

Ultrasound evaluation is the most useful in the diagnosis of hepatic lipidosis but also for identification of concurrent diseases. Most commonly the liver will appear enlarged and diffusely hyperechoic on ultrasound. This finding is not pathognomonic for hepatic lipidosis; it may be seen in normal overweight cats as well as with other conditions such as lymphoma. For actual diagnosis of hepatic lipidosis, it is often sufficient to aspirate of the liver. Cytology reveals cytosolic vacuolization of 80% or more of hepatocytes. If there is a higher than expected amount of inflammation consideration should be given for a liver biopsy as underlying cholangitis may be present and may also need to be treated concurrently. Biopsy of the liver can be pursued via ultrasound guidance, laparoscopy or via laparotomy with the preferred method being laparoscopy. Laparoscopy allows for direct visualization of the liver, sampling of multiple liver lobes, a larger biopsy sample as well as ability to control hemorrhage if it occurs.

Treatment of hepatic lipidosis begins with correcting dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities but the two most important aspects of treatment are nutritional support to provide adequate caloric needs via a feeding tube as well as treating underlying concurrent diseases. In some patients, certain electrolyte abnormalities are exacerbated after treatment has started and this is likely related to refeeding syndrome. Patients should be monitored for hypophosphatemia and worsening hypokalemia. Patients with uncorrected hypophosphatemia are at risk for developing hemolytic anemia. Other signs may be muscle weakness and GI signs. Feeding can be accomplished in early cases via force feeding as well as administration of an appetite stimulant such as mirtazapine or cyproheptadine. In more severe cases force feeding and use of an appetite stimulant often does not work and delays improvement. In these cases a feeding tube should be placed. If anesthesia is not possible a nasoesophageal feeding tube can be placed until the patient is more stable. Otherwise most commonly esophageal feeding tubes are placed although gastrotomy tubes are considered in certain cases. A feeding tube allows for blended food to be administered in the home environment. A high protein, calorie-rich diet is preferred in these patients. Most common diets that are used for home feeding include Iam’s Maximum Calorie as well as Hills a/d. In those cases that also exhibit hepatic encephalopathy, a high protein diet may actually need to be avoided, and in these cases, low protein diet such as Hills L/D, or Royal Canin hepatic diet may need to be considered. It may take several days to increase feedings to equal the resting energy requirement. Tube feedings likely continue for several weeks and clients need to be aware of the commitment of this time frame.

Complications especially associated with nausea may have to be considered. Control of nausea can be accomplished using maropitant citrate (Cerenia) however because this drug is metabolized by the liver a reduced dosage may need to be considered with significant liver dysfunction. Metoclopramide is another drug that should be considered in cases of hepatic lipidosis as it provides anti-emetic but also prokinetic effects. If ileus is significant, certain cases may need a stronger pro-kinetic drug. Cisapride may be used in these cases. In some patients, ondansetron or dolasetron will have better anti-emetic effects compared to other medications and can be substituted in place of other medications. Lastly, in patients that are vomiting frequently Famotidine, a H2-receptor antagonist, are prescribed to help lower the likelihood of lower esophagitis.

Additional considerations for treatment in these patients are supplementation with Vitamin B12 especially in those cases where underlying gastrointestinal disease is suspected. In cats that have had prolonged anorexia Thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency may be of concern and may be noted by vestibular signs, neck ventroflexion, or sluggish pupillary reactions. Oral supplementation is recommended in those cases where clinical signs are noted. Nutraceuticals may be beneficial but significant evidence to document is currently lacking. Both S-adenosylmethionine and milk thistle are anti-oxidants and may be beneficial in recovery in cases of hepatic lipidosis. L-carnitine can be supplemented may improve fatty acid oxidation, decreased ketosis and protect against lipid accumulation. Taurine supplementation may be recommended after prolonged anorexia as this is may reduce cellular toxicity and increase water solubility of bile acids increasing their circulation and renal elimination. Ursodeoxycholic acid may beneficial due to the cholestatic component to this disease however its use is debated for this condition due to rapid improvement and lack of inflammatory or fibrotic changes with this disease as well as the fact that it may worsen taurine deficiency, and promote the formation of hepatotoxic lithocholic acid. When administering supplements, care must be taken to avoid GI upset and reduced compliance by the owner with increasing number of medications and supplements. Cases in which hepatic encephalopathy is suspected may require treatment with lactulose as well as antibiotics to reduce the amount of ammonia in the bloodstream.

In the absence of concurrent disease, recovery rates can be 80% or higher if treatment is initiated early and is continued until the patient is consuming meals consistently. Ideally, total bilirubin concentration should decrease by at least 50% in the first 7-10 days. Hypokalemia, advanced age, low PCV have been reported to be negative prognostic indicators.

* Caution with cats and association with blindness, reduce dose with renal insufficiency

**Neutrophilic cholangitis – NC, Lymphocytic cholangitis – LC, Hepatic Lipidosis– HL

References

- Center SA: Feline hepatic lipidosis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 35:225-269 2005

- Gagne JM, et al.: Histopathologic evaluation of feline inflammatory liver disease. Vet Pathol. 33:521 1996

- Gagne JM, et al.: Clinical features of inflammatory liver disease in cats: 41 cases (1983-1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 214:513 1999

- Harvey AM, Gruffydd-Jones TM. Feline Inflammatory Liver disease. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, ed. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 67 St Louis: Saunders; 2009.

- Hills SL, Armstrong PJ. Feline Hepatic Lipidosis. . In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC eds: Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XV. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2014

- Lucke VM, Davies JD: Progressive lymphocytic cholangitis in the cat. J Small Anim Pract. 25:247 1984

- Marks SL: Update on the diagnosis and management of feline cholangiohepatitis. Proceedings of Waltham Feline Medicine Symposium. Available at VIN

- Marolf AJ et al: Ultrasonographic finidings of feline cholangitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 48: 36, 2012.

- Otte CMA et al: Retrospective comparison of prednisolone and ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of feline lymphocytic cholangitis, Vet J 195, (2):205, 2012b

- Rothuizen J, Bunch SE, Cullen JM, et al.: WSAVA standards for clinical and histological diagnosis of canine and feline liver diseases. 2006 Saunders Edinburgh

- Scherk MA, Center SA. Toxic, Metabolic, Infectious, and Neoplastic liver diseases. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, ed. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 7. St Louis: Saunders; 2009.

- Twedt DC, Armstrong PJ, Simpson KW. Feline Cholangitis. In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC eds: Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XV. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2014

- Wortinger A. Refeeding Syndrome. Proceedings ABVP 2014. Available at VIN.

About the author

|