Urinary incontinence

Analisa Prahl, DVM, DACVIM

Bulger Veterinary Hospital, North Andover, MA

Urinary incontinence (UI) of a beloved indoor pet can cause a significant amount of anxiety in a family due to soiling of carpeting and furniture. This condition can even lead to quality of life dilemmas for pet owners. Urinary incontinence is defined as loss of voluntary control of urination, resulting in leakage of urine from the urinary system to the exterior of the body. While UI has consequences for our clients’ homes, it can also cause significant pathology to our patients. Timely diagnosis and control of this potentially chronic problem will help to ameliorate these concerns.

Physiology of micturition

A basic understanding of urinary bladder and urethral function can help to guide diagnosis and treatment for disorders of micturition, including UI. Urethral sphincter function is responsible for urine retention, and sphincter relaxation results in micturition. Dogs have a functional internal urethral sphincter, which is involuntary, and a true external urethral sphincter, which is under voluntary control. The muscles of the pelvic floor contribute to voluntary urine retention.

During normal urine storage the sympathetic nervous system predominates. The hypogastric nerve relaxes the detrusor muscle via β-adrenergic stimulation. While the urinary bladder is relaxed, urine is collected and stored against a contracted internal urethral sphincter. The internal urethral sphincter is made up of the contracted smooth muscle of the bladder neck and urethra, which undergoes α-adrenergic stimulation from the hypogastric nerve. Voluntary contraction of the external urethral sphincter contributes to increased urethral resistance and helps to maintain continence.

During the voiding phase parasympathetic tone predominates. The stretch receptors of the urinary bladder send signals to the brain, which results in cholinergic stimulation of the detrusor muscle causing contraction with concomitant relaxation of the internal urethral sphincter. With voluntary relaxation of the external urethral sphincter and the muscles of the pelvic floor, normal voiding occurs and the bladder returns to a relaxed state.

Approach to diagnosis and assessment of urinary incontinence

The owner’s impression and description of the micturition problem is the first step in a diagnosis of UI. Appropriate questions should be asked to ascertain when the urinary incontinence began, whether it occurs only when recumbent or sleeping or if the UI occurs during exercise and normal behavior. It is also important to determine if the UI occurs before or after voiding.

The three most common differential diagnoses of UI include urethral incompetence, ectopic ureters, and neurologic disorders. Acquired Urethral Sphincter Mechanism Incompetence (USMI) is typically seen in medium to large breed dogs months to years after ovariohysterectomy. Incontinence often occurs at night or while recumbent and is only intermittent. The volume of urine lost can vary from small drops to large puddles. The exact cause of USMI is not completely understood. Theories include: aging, a relative lack of estrogen, which may affect the urethral responsiveness to adrenergic stimulation, decreases in the length of the urethra, and changes in concentration of gonadotropin releasing hormone. Congenital urethral incompetence is typically seen in female puppies. The UI is usually severe and constant. Dogs with ectopic ureters can present similarly and 2/3 of dogs with ectopic ureters have concurrent urethral incompetence. Dogs with ectopic ureters are more typically female and the majority (91%) have bilateral disease.

A complete physical exam is important and should include evaluation of the size of the urinary bladder before and after voiding. Urinary incontinence in the presence of a large bladder suggests overflow incontinence, and a neurologic work up for lower motor neuron disease would be appropriate. Dogs with severe UI may have urine scald dermatitis or a secondary pyoderma so evaluation of the vulvar region is important. A rectal exam is useful to palpate part of the urethra.

A minimum database is worthwhile to determine if there are reasons for polyuria, which can predispose a pet to UI if they already have low urethral sphincter tone. A urinalysis is important to assess for polyuria and for the presence of a urinary tract infection (UTI). Dogs with UI are at increased risk for a UTI, which can temporarily worsen UI.

Radiography may be indicated in young patients with life long UI, male dogs with UI, or if incontinence occurs within one month of OHE or other surgical procedures. Usually, plain radiographs are not helpful with functional causes or some anatomic abnormalities of UI, so contrast studies such as an excretory urogram and a vaginourethrogram may be indicated. Abdominal ultrasound can also be useful to evaluate for dilated ureters or signs of pyelonephritis. Contrast enhanced CT scans showed a 91% sensitivity rate for detecting ectopic ureters.

Cystoscopy and vaginoscopy are also useful tools to evaluate dogs with UI, especially dogs that failed a medication trial, and dogs that may have ectopic ureters. Cystoscopy can identify persistent hymens, paramesonephric bands (tissue extending from the dorsal to ventral vaginal vault) and is noted to have a sensitivity rate of 95% for identification of ectopic ureters.

Urethral pressure profilometry (UPP) is a technique to record the urethral response to distension created by slow infusion of saline through a catheter. Essentially, a UPP can determine the effectiveness of the urethral sphincter mechanism against a full urinary bladder. It can be useful for diagnosing urethral mechanism incompetence, functional urethral obstruction, and congenital urethral mechanism, incompetence in dogs with ectopic ureters. The average dog with urinary incontinence from urethral incompetence does not require a UPP. Therefore, UPP is typically only available at research and university institutions.

Medical therapy

Alpha-adrenergic agonist medications are the most effective therapy for USMI. These drugs enhance urethral closure via direct stimulation of α-adrenergic receptors on urethral smooth muscle. They are effective in 85 – 90% of dogs with USMI. Side effects can include: hyperactivity, hypertension, rarely anorexia, and weight loss. Alpha-adrenergic agonists are contraindicated in patients with hypertension and should be used with caution in patients with glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy, or diabetes mellitus.

Phenylpropanolamine (PPA) is the most commonly used α-adrenergic agonist for UI. The veterinary licensed product, Proin, is readily available. The typical starting dose is 1.1-1.5 mg/kg PO q 8 hours although even once daily dosing can make a significant difference in dogs with UI. The dose should be tapered to the lowest effective dose. It may only need to be given at night when the primary complaint is nocturia. Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are also α-adrenergic agonists but have found to be less effective than PPA and have more potential side effects.

Hormone replacement therapy is a common treatment for UI and is effective in 50-60% of dogs with UI. Estrogens increase the number and responsiveness of adrenergic receptors on urethral smooth muscle, thereby increasing smooth muscle tone. Because of these changes, estrogens have a synergistic effect with α-adrenergic agonists. Potential side effects of estrogen replacement therapies include bone marrow toxicity, estrus, and behavior changes.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a long acting synthetic estrogen, has traditionally been the estrogen therapy of choice for UI in dogs. The loading dose is 0.1-0.2 mg/kg PO q 24h x 5 days, then the dose is decreased to 0.1-0.2 mg/kg PO once to twice a week or to the lowest effective dose. Higher, prolonged dosing can increase the risk for adverse events such as severe non-regenerative anemia. These risks are minimized when the lowest effective dose is used but complete blood counts should be performed at least every 6 months.

Shorter acting estrogens have also been shown to be effective at controlling UI in dogs. Estriol is a naturally occurring, short acting estrogen found in female dogs. It is administered orally on a daily or every other day basis. It has rapid oral absorption and is cleared within 48 hours. It is typically dosed 2 mg PO q 24 h x 7 days then decreased weekly to the lowest dose that controls UI (usually 0.5 – 2 mg/dog q 24-48h). In a study by Mandigers and colleagues, 67% of estriol treated dogs were continent and 22% were improved. This study evaluated dogs for 42 days and there were no significant side effects seen. Independent long-term studies have not been published but this medication has been used regularly in Europe over the past decade and safety appears to be good.

Recently, estriol has been FDA approved as Incurin™ for treatment of UI in dogs. A multi-site, masked placebo-controlled trial performed by Merck showed nearly 70% of estriol treated dogs were continent or improved within 14 days compared to 37% of placebo controlled dogs. Ninety percent of owners reported no incontinence or improved continence after six weeks of therapy. Side effects were mild and were primarily gastrointestinal (anorexia, vomiting) and estrogenic (swollen vulva, sexual attractiveness, estrous behavior, mammary hyperplasia). No hematologic abnormalities were reported in any of the studies provided by Merck and a study evaluating estriol’s pharmacokinetics found no accumulation. Dosing is similar to what is recommended above: 2 mg PO q 24 h x 14 days, then taper to the lowest effective dose.

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues have recently been investigated for use in controlling UI in dogs. Gonadotropins such as follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) are elevated in ovariohysterectomized dogs. Follicular stimulating hormone and LH receptors have been found on urethral tissues; therefore, LH and FSH may affect urethral tissues and their function. Gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues cause a down regulation of gonadotropin receptors in the pituitary gland, which decreases the production of FSH and LH. In a pilot study conducted by Reichler and colleagues, several types of GnRH analogues were used in dogs with and without PPA. Incontinence was improved or completely achieved for 70-738 days. This lead the same group to do a placebo controlled, double blinded study with the GnRH analogue, leuprolide. Nine of twenty dogs had complete continence after 5 weeks of leuprolide and it lasted for 70-575 days (mean: 261 days). In another 10 dogs, a partial response was seen and UI was reduced by 50%. Curiously, while FSH and LH concentrations were decreased with use of the leuprolide, there was no correlation between decreased concentrations of FSH and LH and level of continence. Also, there was no change in the UPP regardless of whether treated with placebo or with leuprolide. The underlying mechanism of action of GnRH analogues related to UI is unknown at this time but may be related to bladder function as opposed to urethral function. GnRH analogue depot formulations remain difficult to obtain in the USA and at this time use is limited. Compounded products may be available for use.

Urethral bulking agents have been used in dogs for control of UI for more than a decade. Their use was extrapolated from use in people with urinary incontinence. Dogs that have failed medical therapy with α-adrenergics agonists and estrogens may benefit from this procedure. Glutaraladehyde cross-linked collagen has been used often and as such has the most information available. Similar results have been found with particulate extracellular matrix bioscaffold. Since glutaraldehyde cross-linked collagen is no longer being manufactured, other agents are being investigated for use in its place, such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and calcium hydroxyapatite. Continence is improved with placement of bulking agents by creating proximal urethral cushions improving urethral closure. It also appears that placement of the filler lengthens the muscle fibers of the urethra which increases sphincter strength.

The bulking agent is injected through a needle, which is passed through a rigid cystoscope. The agent is placed approximately 1-1.5 cm caudal to the urinary bladder neck. The urethral bulking agent is injected submucosally at three locations, at approximately the 2, 6, and 10 o’clock positions. The bulking agent is injected until a bleb is seen that approaches midline of the urethral lumen. The procedure can often be done on an outpatient basis. Rare complications include temporary urethral obstruction, which is relieved with placement of an indwelling urinary catheter for 24-48 hours.

Collagen urethral bulking is effective in producing continence in 68% of dogs, with an additional 25% improved with concurrent use of medications. Improvement lasted a mean of 17 months with a range of 1-64 months. Dogs that did not achieve complete continence, or dogs in which incontinence resumed, could usually be treated with medications to achieve a longer period of continence. A second treatment with collagen bulking will likely be required in most dogs. Byron and colleagues reported a median duration of continence (with and without additional medication) of 24 months. Ultimately, collagen urethral bulking is an acceptable intervention in dogs that have failed medical therapy, but the duration of continence is variable and there are no markers to help determine the duration of continence in individual patients. Bartges and Callens have presented an abstract looking at 22 dogs that underwent urethral bulking with PDMS with good initial success but long term follow up is still needed.

There are several surgical options for dogs with refractory UI. Colposuspension has been performed, well reviewed, and is best used in patients with a pelvic bladder or a short urethra. The goal of the procedure is to re-position a pelvically placed bladder further into the caudal abdomen to increase abdominal pressure on the bladder neck and proximal urethra increasing urine retention. The vagina is fixed to the ventral abdominal wall repositioning the urethra. Success rates are variable. Rawlings et al found that 50% of dogs were continent at 2 months post operative but only 14% were continent 1 year after surgery. Concurrent medical therapy improved outcome.

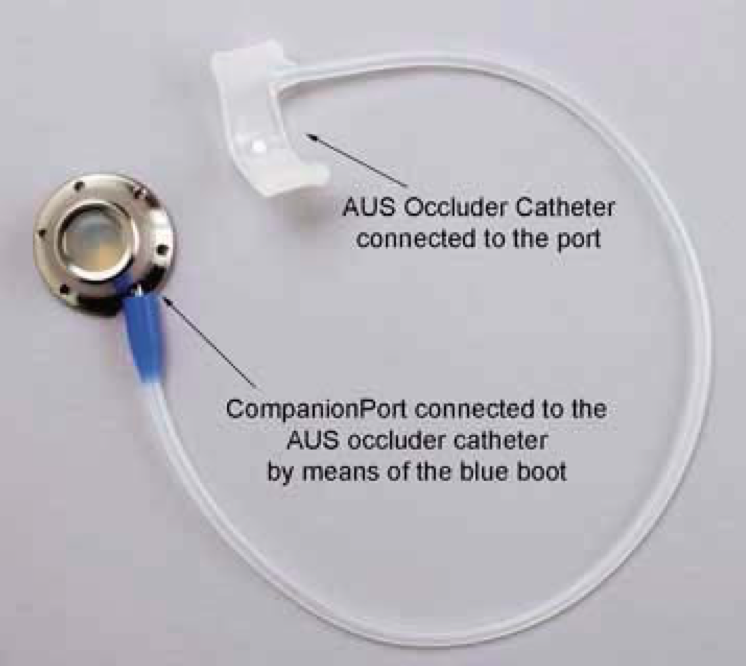

Fig. 1: Urethral hydraulic occluder

Recently, a percutaneously controlled, urethral hydraulic occluder (HO) has been custom designed for use in dogs. The HO includes an incomplete silicone ring that is surgically placed around the extraluminal surface of the proximal urethra (Fig. 1). The ring is closed with suture through two eyelets on each end of the cuff. The cuff is attached to silicone actuating tubing that is attached to a subcutaneous access port. The port can be injected with sterile saline by a veterinarian to increase tone of the silicone ring, thereby improving urine retention. Three of four dogs in the initial clinical trial had long-term (2 years post implantation) improvement of their continence scores. A recent report evaluating 18 dogs with refractory UI again showed good results with placement of a HO. Dogs with owners who followed up regularly for additional inflations of the device, showed functional continence in 92% of dogs and complete continence in 77% of dogs. Placement of the HO device resulted in major complications of urethral obstruction in 3/18 dogs. Obstruction resulted from intraluminal webbing in 1 dog and extraluminal strictures in 2 dogs. All dogs recovered with intervention (urethral stenting) and subsequently achieved functional continence. Because of the potential for major complications with the use of a HO, this procedure should be reserved for those dogs with severe anatomical abnormalities (ectopic ureters, pelvic bladders, short, wide urethras) and severe, refractory incontinence, especially in young dogs who will live with their disease for years.

Troubleshooting

In dogs that are refractory to initial therapy with PPA, consider increasing the frequency to q 12 or 8 hours. Combination of PPA and DES or estriol often results in good results due to their synergistic effects. If UI persists, ensure a full work up has been done evaluating for polyuria, urinary tract infection, and consider imaging or contrast studies to evaluate for structural abnormalities. A referral for a UPP can also be considered. If these studies are within acceptable limits consider urethral bulking procedures if available. If anatomical abnormalities exist consider placement of a HO.

If a patient whose UI has been well controlled suddenly becomes incontinent again, a UA and urine culture should be evaluated. Consider evaluation for development of diseases that cause polyuria. Polyuria can strain an already weak urethral sphincter resulting in worsening UI. Assess for neurologic disease and behavioral disorders. In older animals, consider senility as a contributor to inappropriate urination.

Male dogs

Male dogs rarely present for UI but possible causes include urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence (although it is not well understood), anatomic changes such as ectopic ureter(s), pelvic bladder, and neurologic disease. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence has been noted to occur both as a congenital disease in juvenile male dogs, and as an acquired disease. The dogs with acquired disease may have anatomical abnormalities such as an intrapelvic, proximal bladder neck. Castrated dogs are at greater risk than intact dogs likely due to decreased prostatic weight, which may allow to urethral placement to be intrapelvic. Male dogs with USMI may respond to PPA (40-50%) and those with an intrapelvic bladder may benefit from a vasopexy, which is performed similarly to a colposuspension. Testosterone cypionate may be tried but success is variable. The uses of urethral bulking or HO placement have not been reported at this time.

Take home messages

- Urinary incontinence primarily effects female dogs that have been spayed months to years previously.

- PPA is effective in over 90% of female dogs with USMI.

- Estrogens are effective in about 60-70% of female dogs with USMI.

- Short-acting estrogens such as estriol (Incurin®) are equally effective as DES with less potential for long term side effects.

- PPA and estrogens are synergistic when treating USMI.

- Instillation of bulking agents may be beneficial for those dogs that fail or cannot tolerate common medical therapy.

- Placement of a hydraulic urethral occluder may be beneficial for dogs with refractory urinary incontinence, especially those with anatomical abnormalities.

Further reading

- Aaron, A, et al. 1996. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in male dogs: a retrospective analysis of 54 dogs. Vet Record 139:542-546.

- Adin, CA, et al. 2004.Urodynamic effects of a percutaneously controlled static hydraulic urethral sphincter in canine cadavers. Am J Vet Res 65(3):283-288.

- Bartges, J et al. 2011. Polydimethylsiloxane urethral bulking agent (PDMS UBA) injection for treatment of female canine urinary incontinence – preliminary results. ACVIM Forum, Denver, CO.

- Barth, A et al. 2005. Evaluation of long-term effects of endoscopic injection of collagen into the urethral submucosa for treatment of urethral sphincter incompetence in female dogs: 40 cases (1993-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 226(1):73-76.

- Byron et al. 2011. Retrospective evaluation of urethral Bovine cross-linked collagen implantation for treatment of urinary incontinence in female dogs. J Vet Intern Med 25:980-984.

- Cannizzo et al. 2003. Evaluation of transurethral cystoscopy and excretory urography for diagnosis of ectopic ureters in female dogs: 25 cases (1992-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 223(4):475-481.

- Cleays, S, et al. 2011. Clinical evaluation of a single daily dose of phenylpropanolamine in the treatment of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in the bitch.Can Vet J. May 52(5):501-505.

- Currao, RL, et al. 2013. Use of a percutaneously controlled urethral hydraulic occluder for treatment of refractory urinary incontinence in 18 female dogs. Vet Surg 42:440-447.

- Hoeijmakers, M et al. 2003. Pharmacokinetics of oestriol after repeated oral administration to dogs. Research Vet Sci 75:55-59.

- Lane et al. 1995. Evaluation of results of preoperative urodynamic measurements in nine dogs with ectopic ureters. J Am Vet Med Assoc 206(9):1348-1356.

- Mandigers, PJJ and T Nell 2001. Treatment of bitches with acquired urinary incontinence with oestriol. Vet Record 149:765-767.

- Power, SC, et al. 1998. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in the male dog: importance of bladder neck position, proximal urethral length and castration. J Small Anim Pract 39:69-72.

- Rawlings, C et al. 2001 Evaluation of colposuspension for treatment of incontinence in spayed female dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 219(6):770-775.

- Reichler, IM et al. 2003. The effect of GnRH analogs on urinary incontinence after ablation of the ovaries in dogs. Theriogenology. 60:1207-1216.

- Reichler, IM et al. 2006. Effect of a long acting GnRH analogue or placebo on plasma LH/FSH, urethral pressure profiles and clinical signs of urinary incontinence due to sphincter mechanism incompetence in bitches. Theriogenology 66:1227-1236.

- Richter, KV and Ling, GV. 1985. Clinical response and urethral pressure profile changes after phenylpropanolamine in dogs with primary sphincter incompetence. J Am Vet Med Assoc 187(6):605-11.

- Rose, SA, et al. 2009. Long-term efficacy of a percutaneously adjustable hydraulic urethral sphincter for treatment of urinary incontinence in four dogs. Vet Surg 38:747-753.

- Samii et al. 2004. Digital fluoroscopic excretory urography, digital fluoroscopic urethrography, helical computed tomography, and cystoscopy in 24 dogs with suspected ureteral ectopia. J Vet Intern Med18:271‐281.

- Scott L, et al. 2002. Evaluation of phenylpropanolamine in the treatment of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in the bitch. J Small Anim Pract 43:493-496.

- Wood, JD, et al. 2005. Use of a particulate extracellular matrix bioscaffold for treatment of acquired urinary incontinence in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 226(7):1095-1097.