A pain in the neck: Case report and disease description

Mark Troxel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, MA

A 1-year-old, spayed female Bernese Mountain Dog was presented to the Neurology Department for evaluation of a 4-day history of lethargy, stiff gait and neck pain. The patient had lived in the Boston metropolitan area since two months of age and had no recent travel history. She was up-to-date on vaccines. No known trauma. No other past pertinent medical history.

General physical exam

Within normal limits other than elevated rectal temperature (103.9°F).

Neurological exam

The dog held her head down low to the ground and refused to lift it up (Fig. 1). She had a stiff gait on all four legs. Cranial nerves, postural reactions and spinal reflexes were all normal. Severe hyperpathia was noted on cervical palpation and with range of motion of the head and neck.Neuroanatomic diagnosis

Cervical spinal cord

Differential diagnoses

- Meningitis

- Discospondylitis

- Caudal cervical spondylomyelopathy (CCSM; a.k.a., “Wobbler Syndrome”)

- Intervertebral disk disease (IVDD)

- Neoplasia

Meningitis and discospondylitis are the most common causes of neck pain and fever in young dogs. CCSM is a frequent disorder of young adult, large breed dogs with cervical spinal cord signs, but it was considered less likely in this case given the patient’s fever. Intervertebral disk disease is uncommon at this age, becoming more common after 2-3 years of age.

Diagnostics

- CBC/biochemical profile: Within normal limits

- Cervical radiographs: No significant abnormalities

- MRI neck: Mild bilateral spinal cord compression at C4-5 and C5-6 due to bilateral articular facet hypertrophy

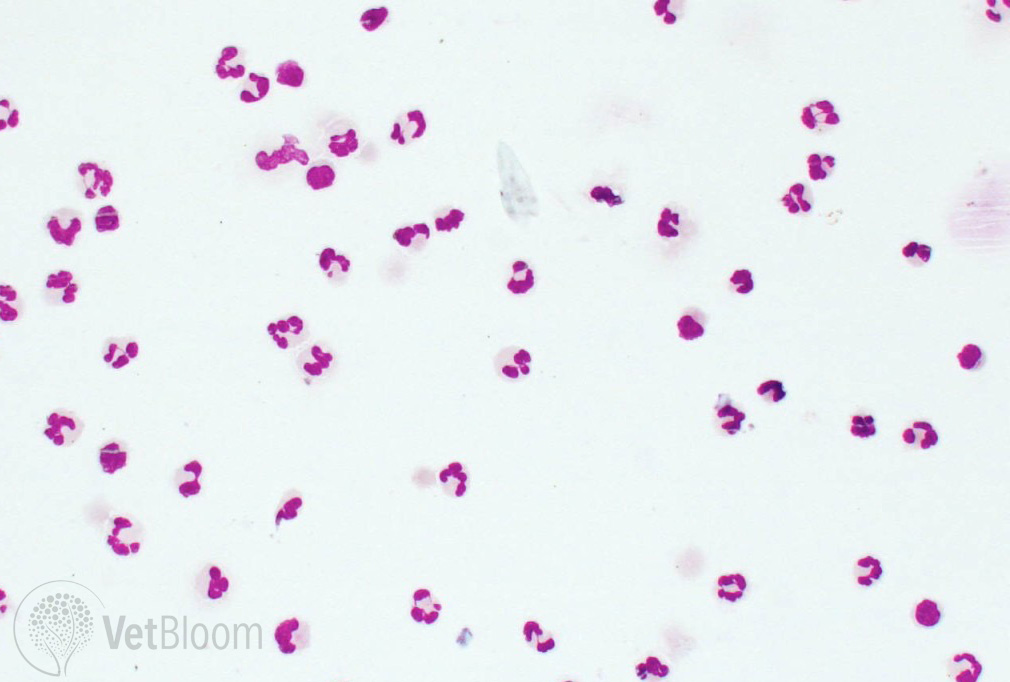

- CSF analysis: Neutrophilic pleocytosis (88% non degenerate neutrophils; Fig. 2) with mildly elevated protein (28.3 mg/dL; normal, < 25) and moderately elevated white blood cell count (69 cells/µL; normal < 5). No bacteria or other etiologic agents found.

- CSF culture & sensitivity: No growth

- Infectious disease titers: Negative for Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia canis, Rickettsia rickettsii, Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, and Cryptococcus neoformans

CBC & biochemical profile were performed to look for an underlying systemic cause for the patient’s clinical signs and as a pre-anesthetic screen. Cervical radiographs were obtained to rule out discospondylitis. It is important to note that discospondylitis may not be radiographically apparent for two or more weeks after onset of clinical signs, but discospondylitis lesions will be visible on MRI much earlier.

An MRI was performed, which showed mild bilateral spinal cord compression at C4-5 and C5-6 due to bilateral articular facet hypertrophy. While this can certainly cause most of the clinical signs observed in this patient, it should not cause fever. CCSM also does not typically cause neck pain as severe as this patient was exhibiting.

A CSF tap was performed because meningitis, especially Steroid-Responsive Meningitis-Arteritis (SRMA), is fairly common in this breed at this age. CSF results were compatible with a diagnosis of SRMA, but infectious disease testing was also performed due to the neutrophilic pleocytosis.

The patient was initially started on anti-inflammatory doses of prednisone (0.5 mg/kg PO BID), minocycline (10 mg/kg PO BID) and clindamycin (10 mg/kg PO BID) pending infectious disease testing. The prednisone dose was increased to 1 mg/kg PO BID after receiving negative infectious disease test results.

Diagnoses

- Steroid-Responsive Meningitis-Arteritis

- Caudal cervical spondylomyelopathy (“Wobbler Syndrome”) – After all of the testing was completed, SRMA was considered the cause of the patient’s clinical signs and CCSM was thought to be a concurrent, incidental finding.

Treatment & outcome

The patient was markedly improved within three days of starting prednisone and was in clinical remission at a two-week recheck exam. The prednisone dose was slowly tapered over the course of 8 months and then discontinued. At some point, clinical signs of CCSM may become apparent, necessitating repeat MRI and CSF analysis to rule out recurrence of SRMA. Surgery for CCSM may be in this patient’s future.

STEROID-RESPONSIVE MENINGITIS-ARTERITIS

SRMA is a relatively common immune-mediated disease of dogs. The cause of the condition is unknown. Activated T-cells have been found in patients with SRMA, suggesting an antigenic stimulus, but no infectious cause has been found to date. A multifactorial etiology is likely. It is possible that there is an environmental trigger that leads to SRMA in patients with a genetic background that predisposes the patient to SRMA. The disease is characterized fibrinoid arteritis and predominantly neutrophilic inflammation of the leptomeninges (arachnoid mater & pia mater) of the spinal cord and brain. In some cases, the arteritis is severe enough to cause ischemic changes in the spinal cord parenchyma. Vasculitis may also be found in blood vessels of the thyroid, heart, and mediastinum.

SRMA is known by many other names, including necrotizing vasculitis, juvenile polyarteritis syndrome, Beagle Pain Syndrome, corticosteroid-responsive meningitis, aseptic suppurative meningitis, and sterile suppurative meningitis.

Signalment: SRMA is most common in Boxers, Bernese Mountain Dogs, and Beagles, but any breed can be affected. Weimaraners and Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers are also over-represented. Age of onset is usually between 6-18 months of age, but has been reported between 4 months and 7 years of age.

Clinical signs: There are two forms of SRMA. The most commonly encountered form is the acute “classic” form of disease. Most patients show signs of fever, hunched and stiff gait with low head carriage (Fig. 1), moderate to severe cervical hyperpathia and lethargy. A less common chronic version of disease occurs with clinical signs of paresis and ataxia if the clinical signs are either treated inappropriately or left untreated.

Diagnostics: Histopathology remains the only definitive diagnostic test for SRMA. However, a presumptive diagnosis usually can be made with the appropriate signalment, clinical findings and compatible test results. Routine laboratory tests (CBC, biochemical profile) are often normal, but a mature neutrophilia may be observed. Cervical spinal radiographs should be performed to rule out other causes of neck pain, such as discospondylitis, atlantoaxial subluxation and fracture/luxation. Tick serology or snap 4DX should also be performed, and the patient started on doxycycline or minocycline if a positive result is found.

Referral for neurology consultation and advanced diagnostics (MRI, CSF analysis) is recommended if blood tests and cervical radiographs are normal and the patient does not respond fully to antibiotics within 2-3 days. MRI of the neck is often normal, but meningeal contrast enhancement may be observed consistent with meningitis. CSF analysis in acute disease typically demonstrates a neutrophilic pleocytosis (Fig. 2) with variable increased protein level and white blood cell count, while chronic disease typically has a mixed cell pleocytosis. Bacterial meningitis is a major differential diagnosis for a neutrophilic CSF, so bacterial culture & sensitivity should be performed. Other infectious diseases that can also cause a neutrophilic pleocytosis in CSF that should be investigated include rickettsial, protozoal and fungal diseases. Several studies have shown elevated IgA levels in both serum and CSF of patients with SRMA, as well as elevated serum C-reactive protein (CRP), acute phase proteins (APP) and alpha2-macroglobulin. While not pathognomonic for SRMA, elevated IgA is rarely observed in other neurological conditions. CRP and APP are frequently elevated in other inflammatory diseases so they should not be used as a sole indicator of SRMA.

Treatment: The mainstay of treatment is an immunosuppressive dose of prednisone, starting at 1 mg/kg PO BID for approximately two weeks, along with pain medications (e.g., opioids, gabapentin, tramadol), as needed. Severe cases may require prednisone at 2 mg/kg PO BID for 2-4 days at onset of treatment before lowering to the dose listed above. If the patient returns to normal by two weeks, the prednisone dose is gradually reduced by approximately 25% every 4 weeks to the lowest effective dose. Other immunosuppressant medications are occasionally needed if there is an incomplete response to therapy, or to help reduce the prednisone dose more quickly due to intolerable side effects. Chronic disease is more difficult to treat and may require additional immunosuppressant medications beyond prednisone at the onset of treatment. Intermittent repeat CSF analysis is ideally performed because it has been shown to be a good indicator of disease remission. As many owners do not allow repeat testing due to the expense of testing and need for repeat anesthesia, patients are often treated based on remission of clinical signs alone. Serum IgA level frequently remains elevated even with successful treatment. However, declining serum CRP level has been shown to be a good indicator of disease remission and may be used instead of repeat CSF analysis to monitor the patient during treatment.

Prognosis: The prognosis for patients with acute disease is usually good to excellent if the disease is treated early and aggressively. Most dogs can be weaned to a low dose of prednisone and many patients can be weaned completely off medications in 6-12 months. The prognosis for the chronic form of disease is fair to guarded and may require long-term treatment, possibly for the remainder of the patient’s life. Recurrence rates are unknown, but appear to be low if prednisone is started early after onset of clinical signs and the dose is not reduced too quickly. A minimum of six months of prednisone is recommended to reduce risk of recurrence.