Canine lymphoma

Mitchell Kaye, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology)

Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital

Posted on 2016-08-02

Lymphoma is one of the most commonly encountered canine cancers, and it is seen frequently in clinical practice. Lymphoma arises from neoplastic lymphocytes. Typically it is first recognized in lymphoid organs (lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bone marrow); however, it can be seen in any location in the body. While dogs of any age can develop lymphoma, it most commonly affects middle-aged to older dogs (median age 6-9 years). The incidence of lymphoma has been estimated to be between 13-24 cases per 100,000 dogs, and in dogs aged 10-11 the annual incidence is estimated to increase to 84 cases per 100,000 dogs. Lymphoma represents up to 25% of canine cancers and 83% of canine hematopoietic cancers.

The cause of lymphoma is likely to be multifactorial, but there are a number of factors that are known to put dogs at increased risk. Certain dog breeds are more prone to lymphoma than other breeds, and there are some breeds that are at higher risk of specific lymphoma immunophenotypes. These findings suggest there is a genetic link in the development of lymphoma. Dog breeds that are at increased risk of developing lymphoma include boxers, bull mastiffs, basset hounds, Saint Bernards, Scottish terriers, Airedales, and bulldogs. Breeds shown to have a lower incidence of lymphoma include dachshunds and Pomeranians. Certain infections have been linked to the development of lymphoma in other species (FeLV in cats, Helicobacter in people), but at this time there has been no recognized link between infection and lymphoma in dogs. Impaired immune function (ex: immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and long-term immunosuppression in organ transplant patients) also increases the risk of developing a lymphoid cancer. Finally, as with many cancers, exposure to certain environmental factors (such as hazardous waste, pollution, tobacco smoke, chemicals, and herbicides) may increase the risk of developing lymphoma in dogs.

Clinical behavior and classification

Most dogs are diagnosed with lymphoma due to the asymptomatic presence of enlarged peripheral lymph nodes; however, at other times dogs may display signs of clinical illness (lethargy, inappetence, weight loss, etc.) depending on the site of involvement and extent of disease. Other clinical signs that may be observed include polyuria and polydipsia secondary to paraneoplastic hypercalcemia and fever (paraneoplastic or infectious secondary to bone marrow suppression).

Lymphoma is actually a diverse group of diseases, and in people over 30 subtypes of lymphoma have been identified. Each of the subtypes of lymphoma may have a different behavior, and accordingly, the most appropriate treatment of each type differs depending on this behavior. There are a number of methods to classify lymphoma including grade, stage, substage, and immunophenotype. While many people have historically thought of canine lymphoma as a single clinical entity, when we have used these factors to classify lymphomas in dogs, we have recognized the same spectrum of behavior that is seen in people.

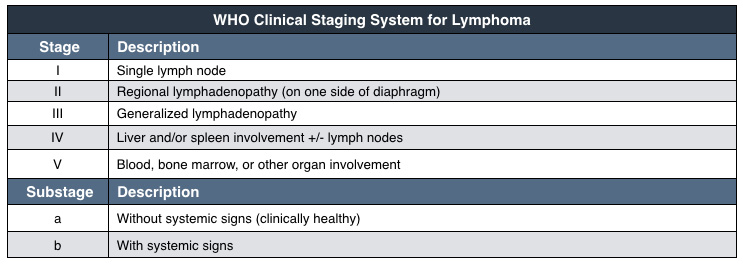

Stage is a measurement of the extent of lymphoma within the body. There are 5 stages of lymphoma (see appendix below), and higher stage lymphomas have been associated with decreased prognosis. Testing to accurately determine the stage can include physical examination, lab work (complete blood count, serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis), imaging (chest radiographs, abdominal radiographs/ultrasound), and bone marrow aspiration. As more of this testing is performed, a phenomenon known as stage migration is seen (meaning that more complete testing is likely to reveal more evidence of lymphoma involvement in the body). However, two recent studies that have evaluated stage migration in dogs with lymphoma have shown that the change in clinical stage associated with more complete testing has not been associated with a change in prognosis.

Substage is an evaluation of the clinical effect that lymphoma has on dogs when they are diagnosed. Dogs that are clinically healthy are classified as substage a, and dogs that have systemic signs associated with lymphoma are classified as substage b. Many veterinary studies have identified substage as an important prognostic factor; however, in contrast to human medicine, at this time there is no consensus in veterinary oncology for specific criteria to use to determine substage.

Histologic classification and grading has also been shown to be an important factor in helping to determine the behavior and prognosis for dogs with lymphoma. Most lymphoma in dogs (70-95%) is classified as high grade (aggressive) and is associated with the typical rapid clinical progression that we typically think about with lymphoma. However, there is also a subset of dogs (5-30%) that have a low-grade (indolent) lymphoma, which is associated with much slower clinical progression and much better long term survival. Therefore, knowing the grade of lymphoma is important to determine an accurate prognosis and treatment plan. Grade is determined by evaluating histologic features of the lymphoma and can only be determined with a biopsy sample.

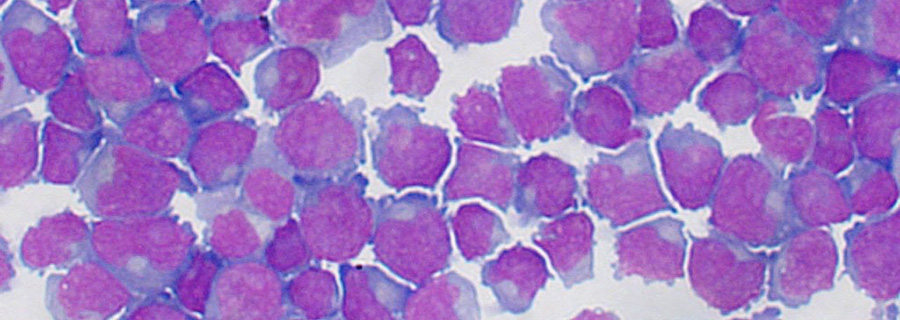

Lymphoma immunophenotype has also been important in helping to classify different types of lymphoma, and it is also one of the most important prognostic factors in high-grade lymphoma. Immunophenotype uses cell surface markers to describe the type of lymphocyte from which the lymphoma has arisen. The gold standard to determine immunophenotype is immunohistochemical staining of a biopsy sample. Immunostaining can also be performed on cytology samples (immunocytochemistry) by certain labs. In addition, there are now molecular techniques (flow cytometry, PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement) that are now being used more commonly in veterinary medicine to determine lymphoma phenotype. Flow cytometry can give a very detailed description of the type of lymphoid population that is present; however, it does not provide information about whether the population is clonal or polyclonal. PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR) is a PCR test that evaluates the B- and T- cell receptors that are present on the surface of most lymphocytes. PARR will determine if a lymphoid population is clonal, and whether the neoplastic population is of B- or T-cell origin.

Treatment

Recommended treatments for lymphoma may vary depending on some of the different classification criteria mentioned above.

Most dogs with lymphoma are diagnosed with high-grade, multicentric lymphoma, and systemic chemotherapy is the recommended treatment course. CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan], doxorubicin [Adriamycin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone) has been associated with the highest response rates, longest remission durations, and longest survival times among first-line chemotherapy protocols in dogs. Other chemotherapy protocols that may be considered as first-line treatments for various reasons include single agent doxorubicin (Adriamycin), single agent CCNU (lomustine), and prednisone. These alternatives are each associated with lower chances of remission and shorter remission/survival times. Although there is no consensus, there is thought among some veterinary oncologists that dogs with T-cell lymphoma might respond better to other chemotherapy protocols. One study that evaluated the MOPP protocol (mechlorethamine [Mustargen], vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine [Matulane], prednisone) for dogs with T-cell lymphoma showed a much higher response rate and longer survival time than expected for this population.

In people, the use of immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies has dramatically improved the success of chemotherapy in treating lymphoma. Rituxan (rituximab) is a monoclonal antibody directed against CD-20, a cell surface marker found on B-lymphocytes. The combination of Rituxan with CHOP chemotherapy (R-CHOP) is now the current standard of care treatment for people with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Monoclonal antibodies are species specific, so we cannot use humanized antibodies in our patient population. However, there are two canine monoclonal antibodies that have been developed for use in dogs with lymphoma. The first targets CD-20 on B-cells (similar to Rituxan) and the second targets CD-52 on T-cells. Preliminary studies seem to suggest that these drugs are well tolerated, with only mild side effects. The anti-CD20 antibody has shown some efficacy in preliminary studies; the anti-CD52 is currently being evaluated in clinical studies. Whether dogs will experience the same survival benefit that is seen in people when monoclonal antibodies are used in combination with traditional chemotherapy remains to be seen.

Bone marrow transplantation is another treatment modality that is sometimes used in people with certain hematopoietic cancers. Much of the preclinical research about bone marrow transplantation was performed in dogs, so there is a large body of literature about performing canine bone marrow transplantation in the laboratory setting. Recently, a few hospitals around the country have also started to offer bone marrow transplantation in the clinical setting for dogs with lymphoma. Based on two recently published studies, bone marrow transplantation after chemotherapy does seem to improve the remission duration and survival time as compared to chemotherapy treatment alone. However, this procedure is quite expensive and is also associated with a very high level of toxicity (including around 10% risk of mortality).

Radiation therapy (RT) is another treatment modality that can be considered for lymphoma. Lymphoma is one of the most sensitive cancers to RT; however, we do not typically use RT due to the multicentric/disseminated nature of most cases. It can be considered for localized forms of lymphoma (such as oral, nasal, mediastinal) or for palliation of a single site of multicentric lymphoma that is causing more significant clinical problems than other involved sites. Staged half-body RT, interposed into a chemotherapy protocol has also been evaluated in treating lymphoma. The results of different studies that evaluate this type of treatment have varied, but some studies suggest that chemotherapy and RT might result in longer remission durations and survival times than chemotherapy alone.

The behavior of low-grade (indolent) lymphomas is very different than high-grade lymphomas, due to the much slower rate of progression. Sometimes, a recommendation for “watchful waiting” is made to closely monitor the behavior of the disease before starting any type of treatment. When chemotherapy is recommended, many oncologists start with less aggressive chemotherapy options such as chlorambucil (Leukeran) in combination with prednisone. There is no consensus about when to start chemotherapy treatment in these patients; however criteria that I use include clinical illness relatable to the lymphoma, significant lymphocytosis, cytopenias secondary to the lymphoma, and significant lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Prognosis

The most important prognostic factor for dogs with lymphoma is tumor grade. High-grade lymphoma is associated with more aggressive behavior, rapid progression, and shorter survival times. Without treatment, the median survival time is 4-6 weeks. With CHOP chemotherapy treatment, the median survival time is about 12 months. Other treatment options have been associated with shorter survival times (doxorubicin – 6-9 months, CCNU – 4 months, prednisone 2-3 months). Prognostic factors for dogs with lymphoma include immunophenotype (B-cell > T-cell), Stage (Stage I, II > Stage III, IV > Stage V), and substage (a > b). Low-grade lymphoma is associated with much longer survival times, and one recent study suggested that the overall survival time (ie, death from any cause) was almost 2 years, and the lymphoma-specific survival time (ie, death due to lymphoma) was about 4.4 years. Many of the factors that have been shown to be prognostic in high-grade lymphoma (stage, substage, phenotype, cell size, systemic treatment) do not seem to influence prognosis in dogs with low-grade lymphoma. While the presence of lymphocytosis does not influence prognosis, the magnitude of lymphocytosis does, and dogs with a lymphocytosis >9,000-30,000/µL may have shorter survival time.

Appendix

|

Further reading

- Barber LG and Weishaar KM. Criteria for the designation of clinical substage in canine lymphoma: a survey of veterinary oncologists. Vet Comp Oncol 2014. doi 10.1111/vco.12086 (epub ahead of print).

- Brodsky EM, Maudlin GN, Lachowicz JL, and Post GS. Asparaginase and MOPP treatment of dogs with lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:578-84.

- Bulman-Fleming J, Rosenberg M, Hansen G, and Klein M. Treatment of canine B-cell lymphoma with doxorubicin with or without an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody: an open-label pilot study. VCS abstract 2014

- Flood-Knapik KE, Durham AC, Gregor TP, et al. Clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical characterization of canine indolent lymphoma. Vet Comp Oncol 2013;11:272-286.

- Flory AB, Rassnick KM, Stokol T, et al. Stage migration in dogs with lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:1041-7.

- Gavazza A, Presciuttini S, Barale R, et al. Association between canine malignant lymphoma, living in industrial areas, and use of chemicals by dog owners. J Vet Intern Med 2001;15:190-5.

- Lurie DM, Gordon IK, Theon AP, et al. Sequential low-dose rate half-body irradiation and chemotherapy for the treatment of canine multicentric lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:1064-1070.

About the author

|