Update on leptospirosis

Julie Fischer, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

Veterinary Specialty Hospital, San Diego, CA

Posted on 2018-01-23 in Internal Medicine

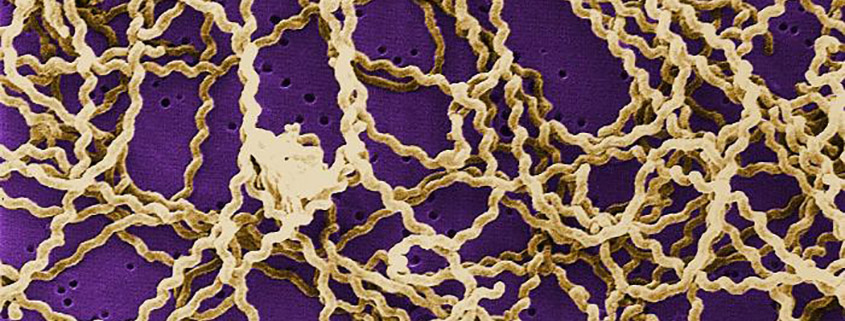

Leptospirosis is a bacterial zoonotic disease with chiefly wildlife and livestock reservoir hosts (only mammals can transmit the disease), caused by Gram-negative, highly motile, obligate aerobic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira, and most commonly transmitted by infected urine contact with mucous membranes or abraded skin. Leptospirosis is considered a seasonal disease, but the seasonality varies in the US with geographic region. Once excreted into a warm, moist environment, organisms can survive for months, and outbreaks are often associated with amount of rainfall or with natural disasters and flooding that spread urine-contaminated water. Leptospires are rapidly deactivated by desiccation. In the US, clinically affected dogs are more likely to live in proximity to outdoor water, to have contact with outdoor water sources, and/or to have indirect exposure to wildlife.

Canine and human clinical signs/syndromes

In dogs, the incubation period is approximately 7 days, and pets are usually presented for nonspecific signs or signs referable to renal or hepatic disease (anorexia, lethargy, vomiting, abdominal pain, icterus, fever), but may also have anterior uveitis, cough (up to 70% of dogs have pulmonary radiographic abnormalities), or arthralgia/ stiff gait.

The incubation period in humans is typically 1-2 weeks, but can range from 2-25 days. Disease course is biphasic with an initial phase of either subclinical to mild signs or febrile, influenza-like signs associated with spiremic replication and spread, followed by symptomatic improvement. The second phase is associated with antibody development and appearance of leptospires in the urine. Most (~90%) of human patients have the anicteric form of disease, with an aseptic meningitis syndrome, +/- uveitis (concurrent or weeks to months later), and many of these patients recover with supportive care alone. The icteric form is more severe, with an initial phase followed by jaundice and renal dysfunction and often pulmonary involvement (cough +/- hemoptysis) and/or hemorrhagic complications (with or without coagulopathy).

What about cats?

Cats are very uncommonly presented for clinically evident leptospirosis, but can become infected (more likely due to direct rodent contact than contact with water) and can shed leptospires in urine, thus qualifying as a potential reservoir species. Interstitial nephritis is present in both naturally and experimentally infected cats. Studies of varied populations of cats worldwide (free-roaming, shelter, US, UK, Australia, Europe, wild, etc.) have shown a seropositivity prevalence of up to 48% (more commonly in the 5-25% range).

The concept of domestic cats as a reservoir species and the possibility of cats as conduits of the organism to dogs and/or humans likely deserve more considerations than we’ve traditionally given it.

Testing and diagnosis

The most common methods of testing for leptospirosis in companion animals have been antibody quantification with microagglutination tests (MAT) and PCR to detect organisms in blood or urine. A MAT titer of greater than 1:800 for vaccinal serovars in a vaccinated animal, 1:800 or greater of any serovar in a non-vaccinated animal, or convalescent titers (collected 2-4 weeks after clinical infection) ≥ four times initial titers is considered supportive of active/recent infection. Because of extensive cross-reactivity, identification of infecting serovar may not be reliable with MAT.

PCR testing of urine or blood may be a more sensitive diagnostic in an untreated animal early in the disease, and ideally both urine and blood are tested separately (not pooled). It is important that PCR be performed on samples collected prior to antibiotic administration, since antibiotics rapidly clear the organism from blood and urine. PCR may be performed on renal tissue (usually post-mortem) as well. Because of unpredictability of spiremia and urine shedding, a negative PCR result does not rule out active leptospirosis.

Rapid diagnostic tests for leptospirosis are now available (Witness® and Test-It™) and recent evaluation has shown similar diagnostic performance of those assays compared with MAT. Both types of testing (rapid and MAT) have better specificity than sensitivity, and for both types sensitivity is relatively low in very early infection. Both types of test are thus better suited to confirm disease than they are to rule it out, and a negative result at admission or relatively early in the disease does not rule out active leptospirosis. False positives (usually weak positives) can result from recent vaccination with bivalent or quadrivalent product, so accurate determination of timing and type of vaccines administered is important for interpretation, particularly of weak positive results.

Treatment

Prompt antibiotic therapy is critical and is based on whether the patient can tolerate oral doxycycline, since most dogs with acute leptospirosis have some degree of gastrointestinal distress at the time of presentation. Generally initial therapy with ampicillin at 20 mg/kg IV q 6 hrs (or other penicillin) is used until the dog feels well enough to switch to oral doxycycline. Third generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone) have also been shown to be effective (first generation cephalosporins are less so), but enrofloxacin was shown less effective than doxycycline, and is not recommended. It is important that dogs receive a full two weeks of doxycycline at 5 mg/kg q 12 hrs or 10 mg/kg q day, once oral medication is tolerated. Antimicrobial resistance fortunately appears to be uncommon in leptospires.

Supportive care for acute kidney injury or hepatopathy is provided in standard fashion, as the clinical picture mandates. Animals with acute kidney injury should be carefully assessed for adequate urine production to rapidly identify developing oligoanuria, avoid volume overload, and potentially refer for hemodialysis in a timely fashion, if possible. Dogs with significant signs of pulmonary involvement, particularly hemoptysis and/or development of ARDS-like signs, have a poorer prognosis and may require mechanical ventilation.

Prognosis

With prompt identification and aggressive fluid and antibiotic therapy, prognosis is fairly good, with an approximately 80% recovery rate. Rate may be higher where hemodialysis is available, and lower for dogs with significant pulmonary involvement. Renal recovery usually occurs over 1-2 weeks, though dogs whose disease is particularly severe or whose treatment was delayed may sustain permanent renal damage. Dogs whose renal values return to normal should still be considered to have IRIS stage 1 (nonazotemic) CKD, and should be presumed at higher risk for future renal injury.

Prevention and Disease Control

Leptospirosis vaccines are effective and contain bacterins for serovars Icterohemorrhagiae, and Canicola, with Grippotyphosa and Pomona added in the quadrivalent vaccine. Vaccinated animals can still become clinically ill, however, since there are many more pathogenic leptospira serovars in the environment. A blanket recommendation for leptospirosis vaccination of dogs in the San Diego area is beyond the scope of this update; however, stronger consideration should be given to vaccination on a case by case basis [Confession: I recently vaccinated my own dogs for leptospirosis for the first time].

Viable organisms are most likely to be shed in urine prior to antibiotic administration (and generally during the first few days of infection), and any personnel handling leptospirosis-suspect dogs should be aware of appropriate measures to protect themselves and prevent contamination of hospital surfaces and materials. Because leptospires are not easily transmitted from dog to dog, isolation housing is not necessarily mandatory if appropriate hygiene measures can be taken. Client education regarding the potential for transmission both to other dogs (and cats) in the house, as well as to human family members is important. Clients should be trained on safe handling of the pet’s urine and on appropriate disinfection methods, and should be advised to promptly contact their physician if a family member becomes ill within the weeks surrounding the pet’s diagnosis. Particular care should be taken with immunocompromised household members or guests.

Treatment of other household dogs (and cats?) with two weeks of doxycycline is recommended, since the disease is communicable and since other pets may have been exposed to the same point source.

The following recommendations for appropriate hospital hygiene practices in managing patients with leptospirosis are paraphrased from the recent European consensus statement on leptospirosis (reference for full consensus statement is below):

- Start doxycycline as early as tolerated to interrupt shedding.

- Promptly disinfect urine-contaminated surfaces with quaternary ammonium compounds, accelerated hydrogen peroxide solution, iodine-based disinfectants, or dilute (1:32) bleach solutions.

- Place cage warning labels as soon as disease is suspected.

- Minimize the movement of dogs with suspected infection around the hospital.

- Walk dogs outside to urinate frequently in an area that can be easily disinfected (ideally minimally porous and without organic material), or place an indwelling urinary catheter.

- Avoid contact between dogs with suspected infection/ contaminated materials, and pregnant or immunocompromised people.

- Wear gloves to handle infection suspects, and wash hands properly before and after handling affected dogs.

- Wear gloves, a disposable gown, a mask, and eye protection when handling soiled bedding or cleaning cages or runs.

- Avoid pressure cleaning contaminated runs to minimize aerosolization of contaminated urine.

- Place soiled bedding in biohazard bags.

- Inactivate infectious potential of urine on surfaces with disinfectant (e.g. by diluting 1:1 with 10% bleach solution).

- Treat all body fluids from affected dogs as medical waste.

- Notify all personnel likely to have (or who have had) direct or indirect contact with a suspect patient of the risks. This includes laboratory personnel that handle body fluids or tissues (i.e., submitted samples should be clearly labeled as leptospirosis suspect).

In a Nutshell

- Leptospirosis is actively being diagnosed in dogs in San Diego county.

- An open index of suspicion and early diagnosis are important for protection of patient, staff, and client health.

- The most common clinical syndromes in dogs are renal and/ or hepatic, but leptospirosis is a rational differential for dogs with any combination of the following: acute kidney injury; polyuria/polydipsia; acute hepatopathy (particularly icteric hepatopathy); pulmonary signs (cough; hemoptysis; acute respiratory distress; interstitial, reticulonodular, or alveolar pulmonary pattern); and isosthenuric renal glucosuria.

- Thrombocytopenia, fever, proteinuria, uveitis, vasculitis, retinal bleeding, and environmental factors favoring exposure (swimming/drinking marshy water, exposure of pet or pet’s food to wild rodents, etc.) should support clinical suspicion of leptospirosis in the presence of a consistent clinical presentation.

- It may be rational to test housemate cats of an infected dog for shedding of leptospira organisms. If other dogs in the house are not tested but just empirically treated, treatment of household cats is reasonable as well.

- Ampicillin (and other penicillins) decrease or eliminate shedding of infective organisms in the urine within 1-2 days, and should be started as soon as possible for acute treatment, particularly in animals that cannot tolerate oral doxycycline.

- Doxycycline is needed to clear the tissue phase of the organism, should be started as soon as tolerated, and should be used for two full weeks.

References / additional reading

- Diagnostic value of two commercial chromatographic “patient-side” tests in the diagnosis of acute canine leptospirosis. Gloor, Schweighauser, Francey, et al. J Small Anim Pract, 58: 154–161. (2017)

- European consensus statement on leptospirosis in dogs and cats. Schuller, Francey, Hartmann K, et al. J Small Anim Pract, 56: 159–179. (2015)

- Serologic and urinary PCR survey of leptospirosis in healthy cats and in cats with kidney disease. Rodriguez J, Blais MC, Lapointe C, et al. J Vet Intern Med. 28(2):284-93. (2014)

- 2010 ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Statement on Leptospirosis: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Treatment, and Prevention. Sykes, Hartmann, Lunn, et al. J Vet Intern Med, 25: 1–13. (2010)

Image at top of page by CDC/ Rob Weyant [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

About the author

|

Dr. Fischer received her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine. She completed an internship in small animal medicine and surgery at the Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada, and a small animal internal medicine residency at Kansas State University. Dr. Fischer served as a clinical instructor at Kansas State before entering private specialty practice in San Jose, California. In 2002, Dr. Fischer established UC Davis’s Nephrology, Urology and Hemodialysis Service in San Diego, coordinating the program until 2009 and becoming a nationally recognized expert in upper and lower urinary tract disease. She has been a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, specialty of Small Animal Internal Medicine, since 2000. Dr. Fischer particularly enjoys the diagnosis and management of upper and lower urinary tract problems, including complicated infections, obstructive ureteral diseases, prostatic diseases, incontinence, and acute and chronic renal failure. Her other special interests include immune-mediated diseases, oncology, and the clinical training of veterinary students and house officers. She served on the ACVIM Small Animal Internal Medicine Credentials Committee, and served on and chaired the Small Animal Internal Medicine Residency Training Committee. Dr. Fischer is passionate about the evolving art of post-doctoral veterinary education, especially the fusion of academic and private-practice advanced training programs. She has published scientific journal articles and textbook chapters on urinary diseases and other internal medicine topics, and speaks locally, nationally, and internationally on topics in nephrology and urology.

Dr. Fischer received her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine. She completed an internship in small animal medicine and surgery at the Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada, and a small animal internal medicine residency at Kansas State University. Dr. Fischer served as a clinical instructor at Kansas State before entering private specialty practice in San Jose, California. In 2002, Dr. Fischer established UC Davis’s Nephrology, Urology and Hemodialysis Service in San Diego, coordinating the program until 2009 and becoming a nationally recognized expert in upper and lower urinary tract disease. She has been a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, specialty of Small Animal Internal Medicine, since 2000. Dr. Fischer particularly enjoys the diagnosis and management of upper and lower urinary tract problems, including complicated infections, obstructive ureteral diseases, prostatic diseases, incontinence, and acute and chronic renal failure. Her other special interests include immune-mediated diseases, oncology, and the clinical training of veterinary students and house officers. She served on the ACVIM Small Animal Internal Medicine Credentials Committee, and served on and chaired the Small Animal Internal Medicine Residency Training Committee. Dr. Fischer is passionate about the evolving art of post-doctoral veterinary education, especially the fusion of academic and private-practice advanced training programs. She has published scientific journal articles and textbook chapters on urinary diseases and other internal medicine topics, and speaks locally, nationally, and internationally on topics in nephrology and urology.