Scratching the surface: Management of corneal ulcers in the ER

Alison Clode, DVM, DACVO

Port City Veterinary Referral Hospital, Portsmouth, NH

New England Equine Medical and Surgical Center, Dover, NH

Posted on 2017-10-24 in Ophthalmology

Corneal ulcers are commonly encountered in the ER, thus adopting a routine approach to the management of ulcers is beneficial, particularly when considering the fast pace and variable caseload of many veterinary ERs. It is important, however, to be thorough in the assessment of such cases, to facilitate appropriate treatment of all potential factors involved in each individual case.

Clinical signs and diagnosis

The most prominent clinical signs of corneal ulceration are non-specific, particularly pain (blepharospasm) and ocular cloudiness. In addition to ulcers, other ocular conditions that may cause a painful, cloudy eye include uveitis and glaucoma. As the treatments for all three conditions vary remarkably, a complete ophthalmic exam is essential to the appropriate diagnosis of ulceration. A complete ophthalmic exam consists of:

- Distant observation (symmetry, wounds, discomfort, etc.)

- Close observation with a focal light source (gross visible abnormalities of the adnexa or globe)

- Menace response, dazzle reflex, direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes

- Schirmer tear test (normal = 15 mm wetting/min)

- Fluorescein stain (retained by corneal stroma in absence of corneal epithelium)

- Intraocular pressure (normal = 10-20 mmHg)

While obtaining an STT may not seem essential to the management of a corneal ulcer, it is extremely important to know if a coexisting tear film abnormality is present, as proper healing of an ulcer requires a healthy tear film. Additionally, while obtaining an IOP may also not seem essential, it is important to know the degree of anterior uveitis present (manifesting as ocular hypotony), which is correlated with the severity of the corneal disease, as well as the possible coexistence of glaucoma (as this may be associated with exposure keratitis).

Following the diagnosis of a corneal ulcer, the next step is classification as simple (superficial, uncomplicated) or complex (deep, complicated), as treatments and prognoses vary significantly. A simple superficial ulcer has mild corneal edema and reflex anterior uveitis, without corneal cellular infiltration or stromal loss, while a complicated deep corneal ulcer has moderate to severe corneal edema and reflex anterior uveitis, with corneal cellular infiltration and possibly stromal loss. A corneal cytology can be performed to facilitate the diagnosis, which may demonstrate neutrophils and infectious organisms (generally bacteria) in complicated cases.

Treatment and prognosis – Simple superficial ulcer

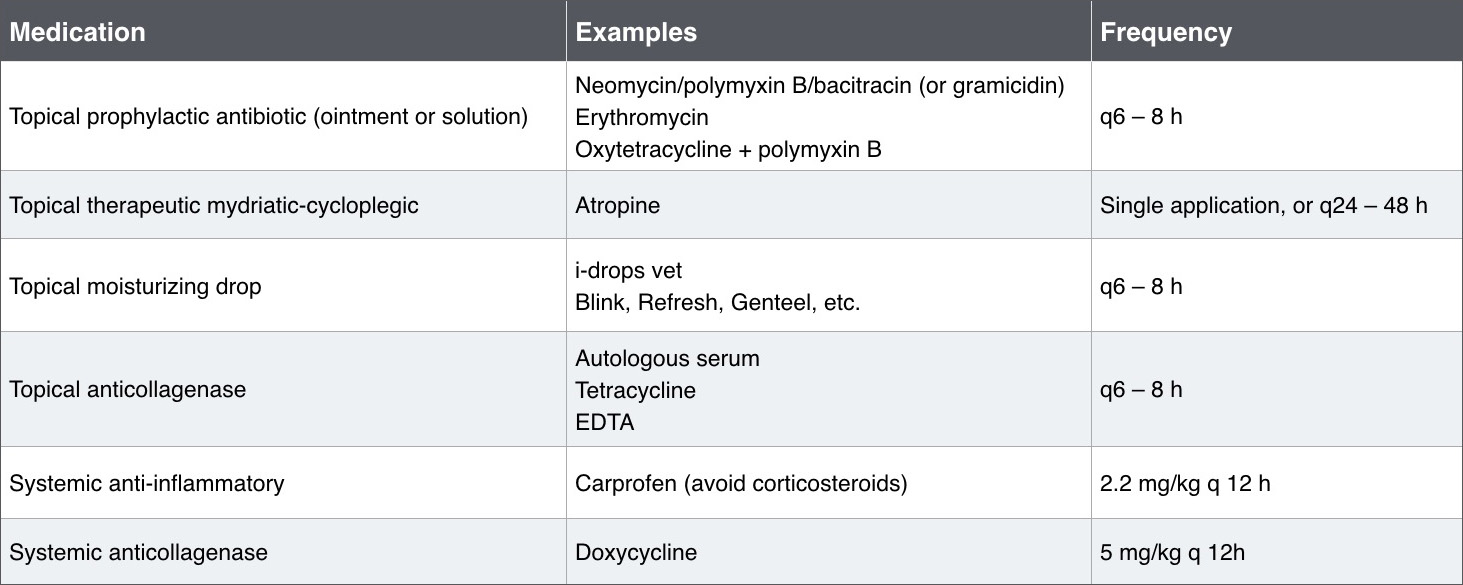

The goals of treating a simple superficial ulcer are to manage pain and prevent infection, with a treatment plan outlined in Fig. 1. Recent evidence suggests that healing may be promoted with the addition of a topical tetracycline, due to the upregulation of TGF-β. In addition to the medications prescribed, an E-collar should also be utilized, and a recheck should be scheduled for 5-7 days, with clear instructions being given as to warning signs suggestive of worsening due to infection (cloudiness, mucopurulent ocular discharge, visible change in appearance of the eye). When providing information, owners can anticipate that an uncomplicated corneal ulcer will heal within 7 days, with minimal scarring.

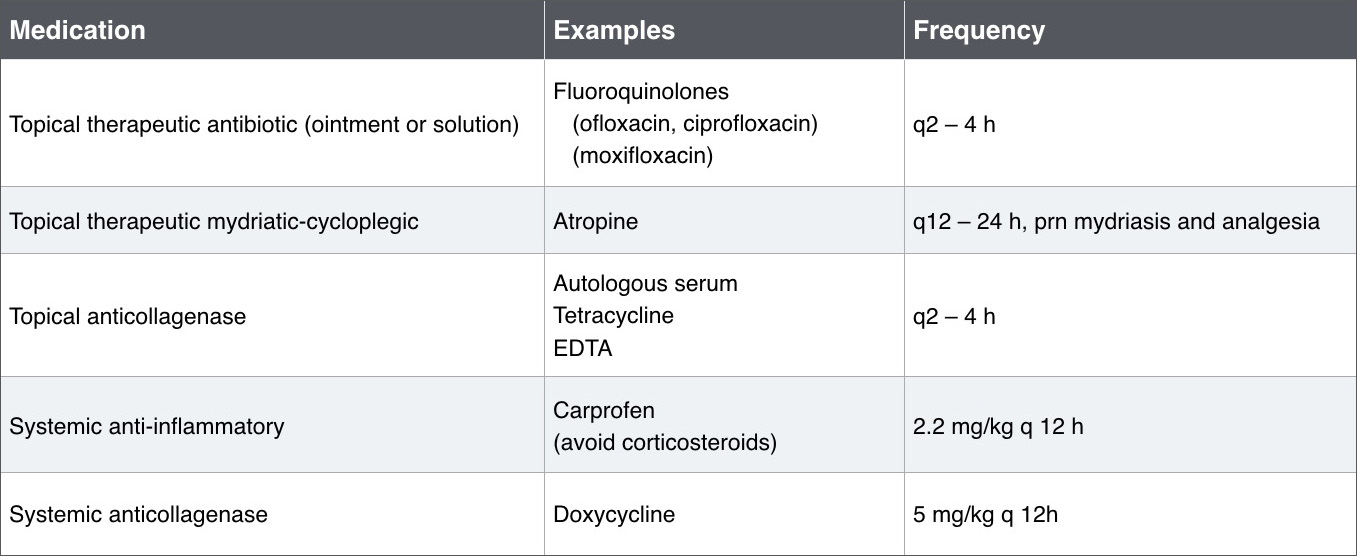

Treatment and prognosis– Complicated stromal ulcer

The goals of treating a complicated stromal ulcer are to manage pain, control infection, and control corneal digestion, with a treatment plan outlined in Fig. 2. In this case, the benefit of a topical tetracycline arises from its ability to control collagenases which digest the corneal collagen, leading to the progressive deepening of an infected corneal ulcer. In addition to the medications prescribed, an E-collar should also be utilized, and a recheck should be scheduled for 1-2 days (unless the patient is hospitalized for more frequent medication administration). When providing information, owners need to be prepared that aggressive therapy will be necessary for a period of a few weeks, and surgical intervention is necessary in some cases. Additionally, progressive ulcers in some cases lead to removal of the eye.

Additional intervention for simple superficial ulcer

In some cases, nonadherent epithelial edges may be evident around a superficial corneal ulceration, and the ulcer may have a history of having been present for >7 days. Such cases are most appropriately referred to an ophthalmologist for assessment as a potential ‘nonhealing’ (spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defect) ulcer, which generally necessitate additional intervention in the form of a grid keratotomy, diamond burr keratotomy, or superficial keratectomy. In an ER setting however, it is reasonable to debride the loose edges from the periphery of the ulcer, in order to provide better comfort for the patient until evaluation by the specialist.

References

- Ledbetter EC. Diseases and Surgery of the Canine Cornea and Sclera. In: Gelatt KN, Gilger BC, Kern TJ, eds. Veterinary Ophthalmology. Vol 2 5th ed. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013; 976-1049.

- Chandler HL, Gemensky-Metzler AJ, Bras ID, et al. In vivo effects of adjunctive tetracycline treatment on refractory corneal ulcers in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010;237:378-386.

About the author

|

Dr. Alison Clode is a native of Spokane, Washington, she completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. She obtained her veterinary degree from Washington State University in 2003 and completed a one-year small animal medical and surgical internship at Colorado State University in 2004. Her residency training in comparative veterinary ophthalmology was completed at North Carolina State University in 2007; she achieved Diplomate status in the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists (ACVO) that same year. Dr. Clode served on the faculty, as an Assistant and then Associate Professor, of the NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine from 2007 to June 2014, at which time she moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and joined Port City Veterinary Referral Hospital. In addition to authoring numerous research articles and book chapters, Dr. Clode has lectured extensively in the US and internationally on topics covering both small animal and equine ophthalmology.

Dr. Alison Clode is a native of Spokane, Washington, she completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. She obtained her veterinary degree from Washington State University in 2003 and completed a one-year small animal medical and surgical internship at Colorado State University in 2004. Her residency training in comparative veterinary ophthalmology was completed at North Carolina State University in 2007; she achieved Diplomate status in the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists (ACVO) that same year. Dr. Clode served on the faculty, as an Assistant and then Associate Professor, of the NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine from 2007 to June 2014, at which time she moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and joined Port City Veterinary Referral Hospital. In addition to authoring numerous research articles and book chapters, Dr. Clode has lectured extensively in the US and internationally on topics covering both small animal and equine ophthalmology.