Diagnosis and treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Ruth Marrion, DVM, PhD, DACVO

Bulger Veterinary Hospital, North Andover, MA

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS; “dry eye”) is one of the most common ophthalmic diseases affecting pet dogs. Despite its prevalence, it is underdiagnosed and therefore often not treated. My goal in writing this article is to encourage veterinarians to perform a Schirmer tear test regularly as part of a complete ophthalmic examination. Once a diagnosis of dry eye is established, treatment can be tailored to the individual patient’s needs.

The red eye

Dogs are often presented to veterinarians for a red, painful eye. The most common causes are:

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

- Corneal ulceration

- Uveitis

- Glaucoma

By performing a complete ophthalmic examination, veterinarians can determine which of these conditions, if any, is responsible for a patient’s condition. When a patient is presented for a “red eye,” I recommend the following tests:

- Schirmer tear test

- Fluorescein stain

- Tonometry

- Menace and palpebral response

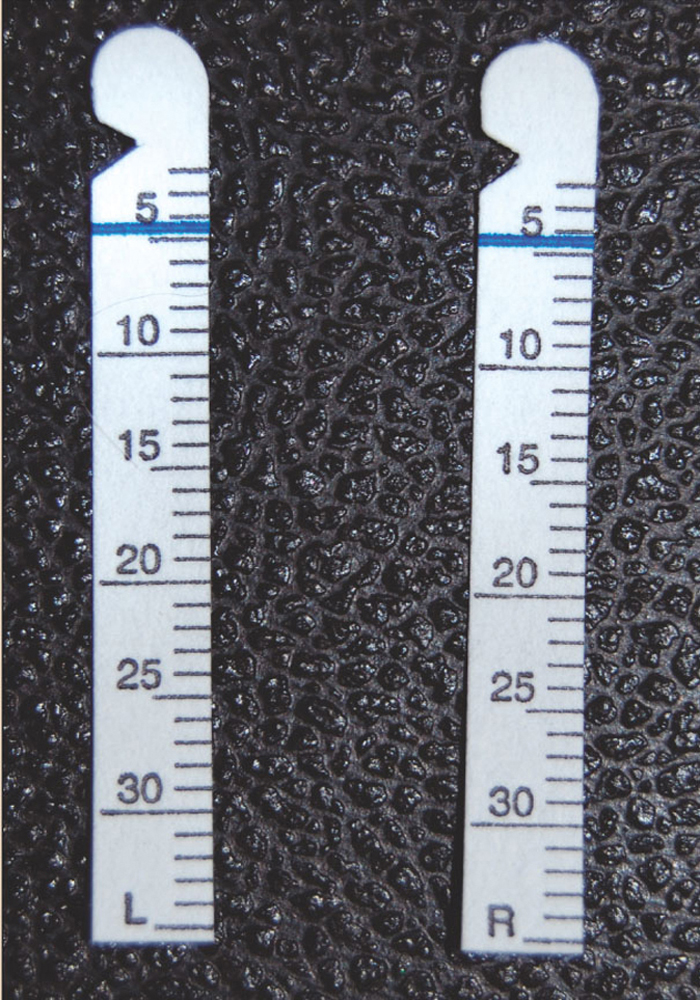

Fig. 1: Schirmer Tear Test Strips. The package is made to be opened at the edge with the squared-off ends of the tear test strip. The examiner should hold this end of the strip and avoid touching the round end.

The Schirmer tear test

Schirmer tear test strips come in packages of two strips, one labeled R and one labeled L (Fig. 1). The package opens to the squared-off handle end of the strips. The examiner is meant to hold this end of the strip, and insert the round end of the strip posterior to the lower eyelid, with the notch at the eyelid margin. The examiner should not touch the round end of the strip, since oil and debris from the hand may affect the tear strip reading.

The tear strip should be held in place for one minute and the number registered on the strip recorded (see video below). Normal tear production in dogs is greater or equal to 15 mm/min. Other tests should be performed FOLLOWING tear measurement, since application of substances to the surface of the eye can alter tear test readings. Applying fluorescein stain or eye wash can result in a falsely increased reading. Conversely, application of topical anesthetic blocks stimulation of reflex tearing and artificially decreases the Schirmer tear test reading.

Additional diagnostics

If the veterinarian determines that a patient has dry eye, there are several questions to be answered:

Does the dog have an ulcer?

Apply fluorescein stain following Schirmer tear test.

Fig. 2: Palpebral response. The examiner touches the eyelid at the medial canthus, and the normal response is complete closure of the palpebral fissure. Incomplete eyelid closure can lead to exposure keratitis and ulceration.

How well does the dog blink?

Many dogs with dry eye also have a poor blink, leading to chronic exposure of the axial cornea and associated ulceration and/or scarring. Test the dog’s palpebral reflex by touching the skin at the lateral and medial canthus (Fig. 2). A dog with a normal palpebral reflex will blink completely in response to a light touch on the periocular skin.

Is a secondary bacterial infection present?

I frequently perform conjunctival cytology to determine if a secondary bacterial infection is present. Most dogs are amenable to this following the administration of topical anesthetic. For this test, I use the handle end of a scalpel blade. Place the end gently in the inferior conjunctival fornix, and move the instrument anteriorly (away from the eye). Analysis of the sample will reveal whether a bacterial conjunctivitis is present.

Treatment of dry eye

The mainstay of treatment for dry eye is a lacrimal stimulant, either cyclosporine or tacrolimus. Cyclosporine was originally shown to be a lacrimal stimulant in the 1980s; treatment with this medication has improved the ocular health of countless dogs with dry eye since that time. There remains, however, a small percentage of dogs in which cyclosporine does not increase tear production and therefore does not relieve signs of dry eye. Tacrolimus has been used more recently to treat dry eye, and has been found to increase tear production in some of the dogs with absolute keratoconjunctivitis sicca that have not responded to treatment with cyclosporine.

According to the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), veterinarians should prescribe medications approved by the FDA whenever possible. Prescribing compounded medications is only acceptable under specific circumstances: When there is no approved animal or human drug that, when used as labeled or in conformity with the extra-label drug use regulations, will, in the available dosage form and concentration, appropriately treat the diagnosed condition.

The only commercially available lacrimal stimulant for dogs is 0.2% cyclosporine in ointment, Optimmune. This medication should be prescribed for initial treatment for dogs with dry eye, used topically two to three times daily depending upon the severity of the dry eye (more detail later).

A veterinarian may wish to investigate the use of compounded medications for lacrimal stimulants if use of Optimmune does not adequately alleviate the signs of dry eye in a patient. This could be because owners have difficulty administering ointments (they may try refrigerating the ointment prior to application), or because application of Optimmune does not result in an adequate increase in tear production (target Schirmer tear test value greater or equal to 15 mm/min). Options include application of cyclosporine 1% or 2% drops, in aqueous solution or oil. Cyclosporine can also be compounded in ointments.

Tacrolimus is a newer lacrimal stimulant which can increase tear production in dogs with dry eye refractory to treatment with cyclosporine. Tacrolimus can be compounded in an aqueous or oil solution to a concentration of 0.02%, or in an ointment at a 0.03% concentration. The advantage of using tacrolimus ointment is that the owner is administering an effective lacrimal stimulant for dry eye IN an artificial tear preparation. This is in contrast to another option: treatment with a lacrimal stimulant in drops, waiting five minutes, then applying artificial tears.

Drops or ointment?

I am often asked whether to prescribe a lacrimal stimulant in a drop or ointment form. There are several factors to consider:

Severity of dry eye: Cases of absolute or severe dry eye are most likely to improve with application of tacrolimus in an ointment preparation. For cases of mild or moderate dry eye, Optimmune or lacrimal stimulants in drop form may be perfectly adequate to achieve the target tear production of 15 mm/min. Treatment twice daily is often adequate for dogs with mild to moderate dry eye; whereas dogs with severe dry eye will likely benefit the most from treatment with tacrolimus in artificial tear ointment three times daily.

Conformational factors: Many dogs with dry eye also have anatomic features that exacerbate the corneal damage from dry eye. Dogs of brachycephalic breeds often have conformational lagophthalmos that results in desiccation of the cornea most exposed in the palpebral fissure, typically the horizontal axial cornea. This desiccation can lead to corneal ulceration in acute cases, and corneal scarring and pigmentation in chronic cases. In severe cases the corneal opacification can result in obstruction of vision. Application of cyclosporine or tacrolimus in an ointment form helps to coat the corneal surface and lessens the amount of ocular pathology from dessication.

Ease of administration: Most owners find eye drops easier to apply than topical ophthalmic ointment. So even in situations where application of ointment would be preferable to drops (severe dry eye, lagophthalmos), it is reasonable to consider prescribing drops if using ointment is simply too difficult for the individual owners in some cases.

Other treatments

Fig. 3: Eye wash. This is to rinse debris from the surface of the eye prior to applying lacrimal stimulants, artificial tears and other ophthalmic medications.

Eye wash: Over the counter eye wash preparations are very useful for removing debris from the ocular surface prior to applying lacrimal stimulants or other medications. I have found that many owners do not understand the difference between eye wash and artificial tears. It may help to use the analogy that eye wash is like a shower for the eye, and artificial tears are like a moisturizer (Fig. 3). Owners should use eye wash PRIOR to applying medications, as needed for accumulation of debris. A dog with severe or absolute dry eye will likely need to be treated with eye wash two to three times daily, whereas a dog with mild to moderate dry eye will not need eye wash nearly as frequently.

Artificial tear supplementation: Treatment with artificial tears can greatly improve ocular health and comfort in dogs with severe and absolute dry eye. Artificial tear preparations are available in most grocery stores and pharmacies in the eye care section. The properties of the different preparations available vary widely, and have to do much more with the viscosity of the formulations than with brand names.

Over the counter artificial tears are made for people with dry eye. Some are liquid with little to no viscosity; the purpose of these preparations is application during the day when people are active. These preparations do not blur vision to any perceptible degree, enabling users to read, drive and perform other activities requiring visual acuity. The problem with these watery drops is that they are effective for less than an hour, necessitating frequent application. This is not a problem for most users but is a deal-breaker for owners of pet dogs.

Preparations for nighttime use by people, also for people with severe dry eye, are thick and viscous, and blur vision. These are effective for hours after application and can keep peoples’ eyes well lubricated at night with no need for repeat application. This type of formulation is appropriate for dogs with dry eye. I tell people to look for an artificial tear that says “severe dry eye, nighttime use, etc. and emphasize that they should be applying an OINTMENT or GEL, not liquid drops. For dogs with severe dry eye not adequately controlled by application of tacrolimus three times daily, application of artificial tear ointment in between times can help to keep the ocular surface moist and healthy.

Topical antibiotics

The presence of dry eye adversely affects ocular health and often predisposes to a secondary bacterial conjunctivitis. Veterinarians can perform a conjunctival scraping to determine if a patient with dry eye has a secondary bacterial conjunctivitis. I recommend application of topical anesthetic prior to the scraping. I use the handle portion of a scalpel blade to take the sample. I rest my hand against the dog, insert the blade handle into the inferior conjunctival fornix, and move the instrument away from the globe slowly and gently. By examining the smear on a microscope slide it is straightforward to determine if a patient has a bacterial conjunctivitis. If this is present, I recommend using a topical antibiotic three times daily for a week. (Read more about conjunctival cytology).

Dry eye is forever

When I am creating a treatment plan for an owner of a dog with dry eye, I try to keep in mind that this is going to be a long term plan and therefore try to make the treatment as easy as possible for the owner. My goal is to use the smallest number of medications. An owner is much more likely to stick with a plan that involves the application of one to two medications two to three times daily, than another that requires the use of three or four medications multiple times daily. For this reason I recommend using “two-in-one” as much as possible, especially for patients with severe dry eye. By this I mean that each medication (lacrimal stimulant, antibiotic) should be in an artificial tear base. If a patient with severe dry eye has a bacterial conjunctivitis I would prescribe a topical antibiotic ointment instead of a drop.

Sample treatment

Severe/absolute keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Morning

- Rinse with eye wash

- Apply tacrolimus ointment

Early afternoon

- Rinse with eye wash

- Apply artificial tear ointment

Late afternoon

- Rinse with eye wash

- Apply tacrolimus ointment

Early evening

- Rinse with eye wash

- Apply artificial tear ointment

Bedtime

- Rinse with eye wash

- Apply tacrolimus ointment

For dogs with severe dry eye and a secondary bacterial conjunctivitis, or a corneal ulcer, the owner may apply an antibiotic in an artificial tear base instead of just artificial tear treatment. It is fine to apply two or three different ointment-based medications at the same time (lacrimal stimulant, antibiotic, atropine for pain relief). If using drops, wait 3-4 minutes between drops, and use ointments following drops.

There are numerous compounding pharmacies from which to obtain compounded lacrimal stimulants and other compounded medications.

Use of topical steroids

Topical steroids are frequently used for dry eye, but are not necessary and can cause adverse side effects if used long term. I have seen many cases of eye problems without a definitive diagnosis treated with topical steroids, with devastating side effects. If an eye problem is caused by an undetected distichia, ectopic cilium, or foreign body, topical steroid use can result in corneal infection and perforation if a corneal ulcer develops. I would like to encourage veterinarians to follow the same principles of steroid use for eyes as for any disease:

- Do not use steroids unless you have a specific diagnosis for which steroid use is indicated

- Have an end point in mind

- Use the least potent steroid for the shortest possible time

- Do not use steroids if there is any contraindication (this would include entropion, aberrant hairs, incomplete blink, or any other condition that could predispose to corneal ulcer formation.

Parotid duct transposition

A small percentage of dogs will not have improvement in clinical signs even with maximal medical therapy. Maximal medical therapy consists of use of eye wash, lacrimal stimulants, and artificial tears as frequently as an owner is able. Parotid duct transposition is a good option for these dogs. It is very important for owners to understand that most dogs following surgery still need to be treated, primarily for mineral deposits from saliva. Treatment often includes topical EDTA ointment to chelate minerals contained in saliva, and oral vitamin C to acidify saliva and decrease mineral deposition.